Photodegradation of Binary Azo Dyes Using Core-Shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Nanospheres

Vol.08No.01(2017), Article ID:73611,21 pages

10.4236/ajac.2017.81008

Eman Alzahrani

Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science, Taif University, Taif, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2017 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: November 9, 2016; Accepted: January 16, 2017; Published: January 19, 2017

ABSTRACT

Photodegradation has emerged as an environmentally friendly method of decomposing harmful dyes in wastewater. In this study, core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/ TiO2 nanospheres with magnetic cores were obtained from synthesised magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles through the precipitation method, the surface of the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles was coated with a silica (SiO2) layer by hydrolysis of tetramethoxysilane (TMOS) as a silica source, and finally, Fe3O4/SiO2 nanospheres were coated with titanium (TiO2) layer using tetrabutyltitanate (TBT) as a precursor through the sol-gel process. The morphology and structure of the prepared materials were characterised by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), X-ray energy dispersive spectrometry (EDAX), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), and atomic force microscopy (AFM). The photocatalytic activities of the prepared core-shell nanospheres were studied using binary azo dyes, namely methyl orange (anionic dye, MO) and methylene blue (cationic dye, MB) in aqueous solution under UV light irradiation (365 nm), and UV-Vis spectrophotometer was utilised to monitor the amount of each dye in the mixture. It was found that 90.2% and 100% of binary MO and MB were removed for 5 h, respectively. The results revealed that the efficiency of the photocatalytic degradation of the core-shell nanospheres was not degreased after five runs that can be used as recyclable photocatalysts. The results show that the performance of the prepared core-shell nanospheres was better than that of commercial TiO2 nanoparticles. Moreover, the magnetic separation properties of the core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanospheres can enable the prepared materials to have wider application prospects.

Keywords:

Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Nanospheres, Core-Shell, Magnetic Photocatalyst, Sol-Gel Method, Binary Azo Dyes, Photodegradation

1. Introduction

In recent years, photocatalysts have attracted many researchers, and the most frequently investigated photocatalysts are titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles because they are chemically stable, can be regenerated, and are recyclable and non-toxic [1] [2] [3] . However, they also have disadvantages, such as the recombination of a generated redox environment, their absorption of a small amount of the UV light irradiation, a large band gap, and low selectivity [4] [5] . Therefore, TiO2-based semiconductors have been of great interest, and great efforts have been made to fabricate and design an ideal structure for TiO2-based semiconductors to improve the efficiency of the TiO2 nanoparticles. Recently, core- shell nanostructure composites have attracted increasing attention because of their various applications, such as catalysis, chromatography separation, drug delivery, and chemical reaction [6] [7] .

Magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (MNPs) have been of great interest because of their magnetic properties, high coercivity, and lack of toxicity. In addition, MNPs are easily fabricated and have high separation efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and a simple operation process [8] [9] [10] . The incorporation of MNPs into a TiO2 matrix can decrease the agglomeration of the nanoparticles, improve the durability of the catalyst, and increase their photocatalytic activity [11] [12] .

The core-shell structure of Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanospheres with an inner layer of SiO2 and an outer layer of TiO2 has attracted attention in recent years [13] [14] . This is because they exhibit good aqueous dispersion and have favourable biocompatibility and readily tailored surfaces [15] [16] [17] . Wang et al. reported on the preparation of core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 microspheres using the sol-gel method modified with polyaniline and their use in the photocatalytic application of a single dye, methylene blue (MB) [16] . In another work, Li et al. fabricated magnetically recoverable Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposites with enhanced photodegradation of rhodamine B [17] . Ma et al. prepared core-shell microspheres using a hydrothermal reaction and used them for the photodegradation of a methyl orange (MO) aqueous solution [18] . In addition, Gao et al. used Fe3O4/ SiO2/TiO2 core-shell nanoparticles with different functional layer thicknesses for the photodegradation of MO under UV light [19] . However, the use of core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanospheres for the degradation of two azo dyes has not been investigated.

In the current study, we aim to take a further step in the application of magnetic core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanospheres as effective photocatalysts. The fabricated core-shell nanospheres were used for the photodegradation of binary azo dyes in aqueous solution, methyl orange and methylene dyes under UV irradiation light. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanospheres have been used for the photodegradation of binary azo dyes. First, the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles were prepared through a precipitation reaction, and then the composite nanospheres were fabricated by sol-gel reaction on the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles. The surface morphology, crystal structure, and properties of the prepared materials were studied using different analytical techniques: XRD, SEM/EDAX, FT-IR, and AFM. Moreover, the recycling of the prepared core-shell nanospheres was checked, and their performance degradation was compared with that of commercial TiO2 nanoparticles.

2. Experimental

2.1. Chemicals

Iron (II) sulphate heptahydrate (FeSO4・7H2O, 98%, M.wt = 151.91 g∙mol−1), sodium nitrite (NaNO3, 99%), tetramethoxysilane (TMOS), tetrabutyltitanate (TBT), methylene blue (MB), and methyl orange (MO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Nottingham, UK). Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) were purchased from Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd. (Mumbai, India). Isopropyl alcohol was purchased from Acros Organics (Loughborough, UK). Ethanol was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). All the chemicals were used without any further purification, and solutions were prepared using distilled water and used for all the preparations. Commercial TiO2 nanoparticles (≥99% trace metal basis, particle size ~0.6 μm) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA). Cylindrical rod magnets (40 mm diameter × 40 mm thick) for settlement of the magnetic nanoparticles were purchased from Magnet Expert Ltd. (Tuxford, UK).

2.2. Instrumentation

A magnetic stirrer and heater were purchased from Fisher Scientific Co. Ltd. (Shanghai, China). A furnace (WiseTherm high-temperature muffle furnace) was bought from Wisd Laboratory Instruments (Wertheim, Germany). X-ray diffraction patterns (XRD) were obtained using a Bruker diffractometer D8- ADVANCE with CuKα1-radiation (Coventry, UK). A scanning electron microscope (SEM) with unit Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDAX) analysis was obtained from JEOL JSM 6390 LA Analytical (Tokyo, Japan). A UV lamp (λ = 365 nm) was purchased from Spectronic Analytical Instruments (Leeds, UK). A UV-Vis spectrophotometer was bought from Thermo Scientific™ GENESYS 10S (Toronto, Canada). The FT-IR spectra were collected in the attenuated total reflectance (ATR) mode using a PerkinElmer RX FT-IR ×2 with diamond ATR and a DRIFT attachment from Perkin Elmer (Buckinghamshire, UK). High-resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM) was used to test morphological features and to produce a topological map (Veeco-di Innova Model-2009-AFM-USA).

2.3. Preparation of the Core-Shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Nanospheres

2.3.1. Preparation of Magnetic Fe3O4 Nanoparticles

Magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles (MNPs) were prepared as described in our previous work [20] . MNPs were obtained by dissolving 3.3 g of FeSO4∙7H2O and 2 g of NaNO3 in 50 mL of distilled water. Then, 20 mL of NaOH solution (2.5 M) was poured into the mixture as it was heated up to 80˚C. The reaction was allowed to proceed at 80˚C under constant stirring to ensure the complete growth of the nanoparticle crystals. After 30 minutes, the resulting suspension was cooled down to room temperature and washed with distilled water repeatedly to remove unreacted chemicals. The magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles were separated using an external magnet and dried in an oven at 50˚C overnight before coating.

2.3.2. Preparation of Fe3O4/SiO2 Nanospheres

The preparation procedure described by [11] with a few modifications. The prepared MNPs (0.5 g) were ultrasonicated in anhydrous ethanol (80 mL) for 1 h. Then, ammonium hydroxide (9 mL) was added to the solution, followed by adding TMOS (3.2 mL). The mixture was stirred for 24 h. Finally, the resultant product was collected using an external magnet and washed with ethanol.

2.3.3. Preparation of Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Nanospheres

5 mL of TBT was dissolved in 40 mL of ethanol. Then, the formed Fe3O4/SiO2 nanospheres were added to the solution. The mixture was stirred for 8 h at 80˚C, and then the product was collected using an external magnet and washed with a mixture of ethanol and distilled water (50:50, v/v). The product was dried in an oven at 60˚C for 8 h, and finally the product was calcinated at 500˚C for 4 h.

2.4. Characterisation of the Prepared Materials

Phase identification and structural analysis of the core-shell nanospheres were carried out using XRD with Cu Ka radiation (λ = 1,5405 Å) in the 2-theta (2θ) range from 20˚ to 80˚. The surface morphology of the fabricated core-shell nanospheres was characterised by SEM analysis after the samples were coated with a thin layer of gold to prevent charge problems and to enhance the resolution. A compositional analysis was performed using EDAX analysis. The chemical functionality of the prepared materials was qualitatively identified using an FT-IR instrument. High-resolution Atomic Force microscopy (AFM) was used for testing morphological features and topological map (Veeco-di Innova Model-2009-AFM-USA). The applied mode was tapping non-contacting mode. For accurate mapping of the surface topology AFM-raw data were forwarded to the Origin-Lab version 6-USA program to visualize more accurate three dimension surface of the sample under investigation.

2.5. Photocatalytic Activity

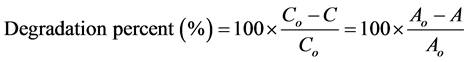

The photocatalytic activity of the composite nanospheres was investigated using mixed dyes (cationic and anionic dyes) in aqueous solution. The photocatalytic experiments were conducted at ambient temperature by mixing 25 mg of the photocatalyst with 100 mL of a mixture consisting of 30 mg L−1 of MB and 30 mg L−1 of MO placed in a cylindrical glass vessel. The solution was stirred magnetically at 700 rmp in the dark for 1 h to reach the adsorption-desorption equilibrium before exposure to the UV lamp [21] [22] [23] . The photocatalytic experiment was performed under the UV lamp with constant magnetic stirring during the reaction. A 2 mL aliquot was withdrawn from the mixture solution at 60 min intervals. The disappearance of MO and MB was spectrometrically monitored as a function of irradiation time using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer at a wavelength between 350 and 800 nm. The percentage of degradation was calculated using the following Equation (1) [24] [25] [26] :

(1)

(1)

where Co is the initial concentration of the dye solution, C is the concentration of the dye solution after photoirradiation in a selected time interval (1 h). Parameters Ao and A are the absorbance of the dye solution at the initial time and at any time theatre, respectively.

The stability of the materials was checked by a recycle usage experiment. This was performed after separation of the photocatalyst from the degraded solution using an external magnet; the materials were washed with distilled water and then with ethanol and dried in an oven at 100˚C for 2 h. Then, the materials were reused again for the second run of removal of the binary dye mixture, and this method was repeated for 5 application runs.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation of the Core-Shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Nanospheres

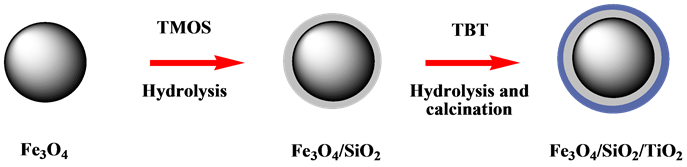

The aim of the current work was to fabricate the core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanosphere composite to use them as a photocatalyst for the degradation of binary azo dyes under UV light irradiation. Scheme 1 presents the schematic route for fabrication of the core-shell nanospheres. The first step was the fabrication of the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles prepared using our previous work [20] through the chemical precipitation method. The preparation of the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles was performed by mixing FeSO4∙7H2O with NaNO3 in purified water, followed by the addition of NaOH solution for the precipitation of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles (black powder). The magnetic core of the core-shell nanospheres can make separation of the materials easy with the assistance of an external magnet [27] [28] .

The second step was the preparation of the core-shell nanospheres, which was based on two steps. First, the surface of the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles was coated with a thin layer of silica by using a hydrolysis reaction with TMOS as the silica source with the aid of ultrasonication; as a result, the SiO2 layer coated the surface of magnetic nanoparticles (brown powder). It is important to mention

Scheme 1. The synthetic route to the magnetic core-shell structured nanospheres (Fe3O4/ SiO2/TiO2) through the sol-gel method using TMOS and TBT as precursors, respectively.

that hydrophobic magnetic nanoparticles cannot be easily coated with a TiO2 layer; therefore, coating the magnetic core with a semi-hydrophobic SiO2 layer is very important [29] . In addition, an SiO2 layer can be easily etched onto the nanospheres, making space for absorption of polluted materials [11] . The third step was hydrolysis of the surface of the Fe3O4/SiO2 composite through the sol- gel method using TBT as precursor. This step results in an additional thin layer of TiO2 on the nanospheres (red brown powder), which acts as a photocatalyst to decompose the harmful dyes.

The magnetisation of the prepared materials was checked by placing an external magnet from the glass vessels containing the fabricated materials, as shown in Figure 1. It was found that all the fabricated materials were attracted to the magnet field and separated from the solution in less than 30 s, leaving clear solutions and confirming that the prepared composite nanospheres have magnetisation properties.

The core-shell nanospheres were studied by XRD analysis. Figure 2 presents the X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of the core-shell nanospheres, showing the diffraction peaks [2θ: 23.18˚ (200), 30.22˚ (220), 35.68˚ (311), 43.34˚ (400), 53.09˚ (422), 57.40˚ (511), and 62.98˚ (440)] [19] [30] . It was found that the material was composed of the tetragonal phase of anatase TiO2 and the orthorhombic phase of the Fe3O4 magnetic phase [18] . Therefore, it is suggested the hybrid composed of the anatase and Fe3O4 magnetic phase, as well as the core-shell nanospheres, are still superparamagnetic or ferromagnetic in nature [31] . At the same time, it was found that there were no peaks corresponding to a crystalline SiO2 layer. This is because the SiO2 layer on the Fe3O4 magnetic core is

Figure 1. Digital illumination photographs of dried fabricated materials after separation from solution by placing an external magnet near the glass vessels for 30 s.

Figure 2. XRD pattern of the core-shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanospheres.

amorphous and does not change the structure of the Fe3O4 magnetic core [12] [32] [33] [34] .

The morphology of the prepared samples was studied using SEM analysis, as shown in Figure 3. The magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles, shown in Figure 3(a), have an irregular crystalline form, and the surface morphology analysis demonstrates the agglomeration of many ultrafine particles because of their small size and magnetism [20] [35] [36] . Figure 3(b) shows that the surface of the Fe3O4/ SiO2 nanospheres was smooth compared to that of the naked Fe3O4 nanoparticles because of the coating of the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles with the SiO2 layer [32] [33] [37] . Figures 3(c)-3(f) shows micrographs of a Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposite sample using different magnifications, illustrating that significant morphological differences could be observed between the Fe3O4 nanoparticles and the Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposites. The micrographs of the composite are rough and porous, which can enhance the photocatalytic activity [16] [38] . In addition, they have a pomegranate-like structure, which can enable them to contact better with dyes and achieve high degradation [39] .

In addition to the use of SEM analysis, the fabricated materials were further studied using EDAX analysis to recognise the chemical composition of the fabricated materials. Figure 4 shows the energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDAX) spectra of Fe3O4, Fe3O4/SiO2, and Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposite samples between 0 kV and 10 keV. The EDAX spectrum of the Fe3O4 sample showed strong peaks of Fe and O (Figure 4(a)). A new peak at 1.739 keV was observed in the Fe3O4/SiO2 sample for the Si element, which confirms the formation of an SiO2 shell on the surface of the magnetic nanoparticles (Figure 4(b)). In the EDAX spectrum of the Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposite sample, it was found that besides the peaks for the Fe, O, and Si elements, a new peak at 4.508 keV was observed, which was related to the Ti element, confirming that a TiO2 layer successfully coated the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanoparticles (Figure 4(c)). A similar result was obtained by [11] . Table 1 presents a composition of 61.52% iron and 38.48% oxide in the Fe3O4 sample, while 17.39% silicon was found in the Fe3O4/SiO2

Figure 3. SEM images of Fe3O4 (a), Fe3O4/SiO2 (b), and Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposites (c)-(f).

Figure 4. EDAX spectra of (a) Fe3O4, (b) Fe3O4/SiO2, and (c) Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposites.

Table 1. Elemental composition of the fabricated materials determined by EDAX analysis.

sample, and 10.51% titanium was found in the Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 sample without any elemental impurities present in the fabricated materials.

An FT-IR spectrometer was utilised to characterise the composition of the prepared materials. Figure 5(a) depicts the IR spectrum of naked magnetic nanoparticles showing a band at around 561 cm−1, which can be attributed to the stretching vibration of the Fe-O bending vibration. Moreover, there was no band related to adsorbed water (1600 and 3400 cm−1) that was observed by other groups [33] [40] . As shown in Figure 5(b), the IR spectrum of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles coated with an SiO2 layer has a larger signal compared with the spectrum of the bare magnetic nanoparticles, and the main bands on the spectrum were 1091, 805, 693, and 573 cm−1. The bands at 1091 and 805 cm−1 indicate the asymmetric stretching and symmetric stretching vibration bonds of Si-O-Si and Si-OH bonds, respectively [41] [42] . The wavenumber around 693 cm−1 is attributed to the symmetric stretching vibration of Si-O-Si bonds, and the wavenumber around 573 cm−1 is related to Si-O-Fe bonds [43] . All of these results confirm the coating of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles with an SiO2 layer. Figure 5(c) displays the IR spectrum of Fe3O4/SiO2 nanocomposites after coating with an additional thin layer of TiO2. The absorption band at 500 - 700 cm−1 is related to the Ti-O-Ti or Fe-O stretching vibrations [44] [45] . However, the band at 1640 cm−1 that was observed by other groups [14] [43] and related to Ti-O-Si vibration, was not observed in this study.

The nanosphere diameter and the surface properties of fabricated materials were analysed by atomic force microscopy (AFM), as AFM investigation can give qualitative and quantitative information on the diameter of the fabricated materials [46] [47] [48] . Figure 6 shows the three-dimensional (3D) AFM images of the fabricated materials obtained using the AFM technique. It can be clearly seen that the flat surface of the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles was smooth, uniform, and the mean diameter ranged from 20.6 to 43.6 nm. After coating of the magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles with an SiO2 layer, the mean diameter was slightly increased and estimated in the range of 22.2 - 44.3 nm. The three- dimensional AFM image of the core-shell nanospheres showed that the mean diameter was increased to 37.6 - 45.5 nm confirming the coating of the Fe3O4/ SiO2 nanoparticles with a TiO2 layer.

3.2. Photocatalytic Study of the Core-Shell Nanospheres

The evaluation of the photocatalytic activity of the synthesized core-shell

Figure 5. FT-IR spectra of (A) Fe3O4, (B) Fe3O4/SiO2, and (C) Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 nanocomposites.

Figure 6. Three-dimensional AFM images recorded for the fabricated materials.

nanospheres was carried out using two different harmful dyes, MO and MB, in aqueous solution under UV light [49] [50] . The photocatalytic activity of the photocatalyst was tested by mixing 100 mL of the dye solution with the photocatalyst (25 mg). After adsorption-desorption equilibrium between the photocatalyst and the dye molecules was achieved for 1 h in the dark, the dyes were tested with the photocatalyst under a UV lamp (365 nm) at 1 h intervals, and 2 mL of suspension was extracted to determine the dye concentrations. Figure 7 displays a photograph showing a change in the colour of the binary dye solution with photodegradation time. It was observed that the colour of the dye solution was green (the colour of MO is orange while that of MB is blue resulting in a green solution). It was found that when the exposure time to the UV light irradiation was increased, the green colour of the dye solution gradually diminished. Later, the colour of the dye solution changed to yellow and finally after 5 h of exposure to the UV lamp, the solution became transparent solution indicating the destruction of the chromophoric structure and the complete photodegradation of the two dyes [51] .

The change in the concentration of the dyes was assessed by monitoring the absorbance of the dyes for different irradiation times (0 - 5 h) using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer in the range of 350 - 800 nm. Figure 8 shows the UV-Vis spectra of MO and MB in aqueous solution for different periods of UV light illumination. The maximum wavelengths (λmax) of MO at 465 nm and MB at 662 nm were used to study the effect of the photocatalyst on the photodegradation of

Figure 7. Photograph showing a change in the colour of binary dyes with increasing exposure time (0 - 5 h) to the UV lamp (365 nm) indicating that with increased exposure to UV light irradiation, the colour of the dye mixture steadily disappeared and finally the dye became nearly colourless.

Figure 8. Optical absorbance spectra monitoring the photocatalytic degradation process of the dyes, MO (30 mg L−1) and MB (30 mg L−1) in 100 mL of volume using 25 mg of the core-shell nanospheres in the presence of the UV lamp (365 nm) and a temperature of 25˚C ± 0.1˚C at different time intervals (0 - 5 h) for absorbance measurements of 350 - 800 nm.

MO and MB at the same time. It was observed that with increasing exposure time to UV light irradiation, the UV-Vis absorption peaks corresponding to the dyes gradually weakened illustrating the degradation of the dyes. After 2 h of irradiation, no absorption peak was observed for MB, indicating the complete degradation of MB while the weak MO bands indicated that MO required more time to complete decomposition. After 5 h of irradiation, both dyes were completely decomposed as the absorption peaks of the dyes disappeared and no other products detectable by the UV-Vis spectrophotometer were found in the reaction mixture.

Table 2 presents the change in the absorbance and the peak position of MO and MB as well as the photodegradation percentage of MO and MB with different irradiation times. It was found that the absorbance of MO and MB decreased with increased exposure to UV light irradiation. In addition, the results indicate that the peak positions of both dyes were shifted to the shorter wavelength and had an obvious hypsochromic shift (blue shift of the band gap). Similar phenomena have been reported when utilising TiO2 nanoparticles as a photocatalyst for the photodegradation of malachite green under UV light [52] . This is due to the decomposition of the dye molecules into mono-substituted aromatics, CO2, and H2O under photocatalytic degradation [53] . It was found that MB was degraded completely in 5 h, while 90.20% of MO was degraded indicating that the photodegradation of MB was faster than that of MO.

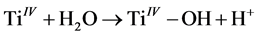

It is very important to note that the photodegradation of the dye depends not only on the formation of hydroxyl radicals at the interface of the nanospheres but also on the ability of the dye to adsorb onto the surface of the photocatalyst, as the physical and chemical properties of different dyes are not the same, which means that the two dyes compete for adsorption at the surface of the photocatalyst [54] [55] [56] [57] [58] . Moreover, the surface of the core-shell nanospheres dispersed in distilled water is covered by hydroxyl groups, as shown by Equation (2) [59] :

(2)

(2)

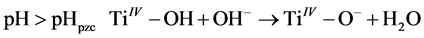

The surface charge of TiO2 is a function of the solution pH, which is affected by the reactions that occur on the surface charge, as shown by Equations (3) and (4):

Table 2. Photochemical degradation of MO and MB using core-shell nanospheres.

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

When the pH of the solution is lower than pHIEP (pHpzc), a positive charge forms on the surface of the core-shell nanopheres (Equation (3)), which means photodegradation in favour of MO (anionic dye). If the pH of the solution is higher than pHIEP, a negative charge forms on the surface of the core-shell nanospheres (Equation (4)), which means photodegradation in favour of MB (cationic dye). In the current work, the pH value of the initial solution of the binary dye mixture was, 7.02 while the pHpzc of the TiO2 layer is 6.5 [60] .

Figure 9 depicts the curves of photocatalytic decolouration showing a comparison of the degradation percentage of MO and MB. The experimental results reveal that in the blank experiment, in the absence of the photocatalyst and UV

Figure 9. Curves of photocatalytic decolouration showing the comparison degradation percentage of MO and MB as a function of time. The bottom curve represents dye only (without a photocatalyst and UV lamp). The second curve represents dye exposed to UV irradiation in the absence of a photocatalyst. The third curve corresponds to dye mixed with the core-shell nanospheres in the absence of UV irradiation. The fourth curve corresponds to dye in the presence of the core-shell nanospheres and UV irradiation showing the efficient photocatalytic degradation of MO and MB.

lamp (self-degradation of dyes), there was no obvious degradation and the degradation percentage was less than 5% for both dyes after 5 h. In addition, it was found that when using the UV lamp (photoinduction) without a photocatalyst, the decolourisation percentage reached 17% and 19% for MO and MB, respectively, which may result in a low degree of photodegradation percentage for both dyes. When using the core-shell nanosphere as a photocatalyst without using a UV lamp, the photocatalytic percentage of the dyes was only 24% and 28% for the MO and MB solution, respectively, indicating that the decolourisation efficiency of the dyes in the presence of the photocatalyst without UV lamp irradiation was insignificant. The value of the photocatalytic percentage was found to be 90.2% and 100% for MO and MB, respectively, indicating that the highest photocatalytic percentage of the dyes among the four experiments was achieved when using a photocatalyst in the presence of UV light irradiation.

3.3. Comparison with Commercial TiO2 Nanoparticles

The performance of the fabricated core-shell nanospheres in the degradation of the binary dyes (MO + MB) was compared with that of commercial TiO2 nanoparticles under the same conditions. Figure 10 presents a comparison between the fabricated core-shell nanospheres and the commercial TiO2 nanoparticles. As indicated, the decolourisation percentage of MO was 82.6% when using the commercial TiO2 nanoparticles, while 90.2% of the MO dye was decomposed when using the core-shell nanospheres. In addition, 88.4% of MB was degraded when using the commercial TiO2 nanoparticles, while MB was degraded completely when using the core-shell nanospheres. It has been reported that dye impurities were still found when using TiO2 nanoparticles as a photocatalyst indicating the low photocatalytic activity of the TiO2 nanoparticles [61] [62] [63] . These results showed that the core-shell nanospheres had high photocatalytic activity compared with the commercial TiO2 nanoparticles in terms of decolourisation of the binary mixture of MO and MB, so this process could be considered a promising process for removal of harmful dyes from the environment.

Figure 10. Comparison of the degradation percentage of MO/MB binary systems with commercial TiO2 nanoparticles and the fabricated core-shell nanospheres.

3.4. Recycling of the Core-Shell Nanospheres

The cyclic stability of the fabricated core-shell nanospheres for the photocatalytic degradation was evaluated. After the separation of the photocatalyst from the degraded solution using an external magnet, they were washed with distilled water and ethanol and then dried in an oven at 100˚C for 2 h, the materials were reutilised and the cyclic stability was checked by monitoring the photocatalytic activity of MO and MB (newly added dye) during five cycles of use as a photocatalyst under UV irradiation. As shown in Figure 11, it was found that the recycled core-shell nanospheres did not show any change in the photocatalytic activity even after five cycles of use without a reduction in the photodegradation of MO and MB indicating the high chemical stability of the fabricated materials. In addition, the experimental results showed that the magnetic properties of the core-shell nanospheres can make separation of the materials from the degraded solution easy.

The performance of the core-shell nanospheres was compared with that of previous reported nanomaterials used as a photocatalyst for a binary system. Table 3 shows a comparison of the removal percentage using the core-shell nanospheres with the removal percentage of binary dye systems using other nanomaterials in the literature. It was found that the photocatalytic activity of the core-shell nanospheres was effective and better than that of other reported photocatalysts. Although the steps of the fabrication of the nanospheres are too long, the fabrication procedure was simple and low cost, and the materials have the best photocatalytic activity to remove toxic organic dyes from the environment and can be easily separated from solution using an external magnet.

4. Conclusion

In summary, magnetic core-shell nanosphere materials composed of Fe3O4/SiO2/ TiO2 nanocomposites were fabricated from a combination of precipitation

Figure 11. Five cycles of photocatalytic degradation of MB and MO using the core-shell nanospheres.

Table 3. Comparison of the photocatalytic degradation percentage for the prepared core- shell nanospheres with that of other nanomaterials as previously reported.

reactions, and a silica layer was coated on the surface of the magnetic nanoparticles using the sol-gel process, followed by coating of the Fe3O4/SiO2 nanocomposites with an outer layer of TiO2 via the sol-gel process. The fabricated materials were used in the photodegradation of binary dyes under UV light irradiation, and it was shown that core-shell nanospheres had high photodegradation efficiency. In addition, the current study reveals that the fabricated core-shell nanospheres displayed good magnetic properties at room temperature, which can create a fast separation photocatalyst after reaction. The results indicate that after five cycles of use, the high photocatalytic activity of the core-shell nanospheres did not decrease. Therefore, the core-shell nanospheres are promising agents and highly beneficial for various potential applications for the treatment of textile effluents containing harmful organic dyes. In addition, the results suggest that the prepared materials can be extended to various applications, such as purification, catalysis, and separation processes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Cite this paper

Alzahrani, E. (2017) Photodegradation of Binary Azo Dyes Using Core-Shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Nanospheres. American Journal of Analytical Che- mistry, 8, 95-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ajac.2017.81008

References

- 1. Singh, S., Mahalingam, H. and Singh, P.K. (2013) Polymer-Supported Titanium Dioxide Photocatalysts for Environmental Remediation: A Review. Applied Catalysis A: General, 462-463, 178-195.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2013.04.039 - 2. Yola, M.L., Eren, T. and Atar, N. (2014) A Novel Efficient Photocatalyst Based on TiO2 Nanoparticles Involved Boron Enrichment Waste for Photocatalytic Degradation of Atrazine. Chemical Engineering Journal, 250, 288-294.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2014.03.116 - 3. Yuliati, L., et al. (2016) Modification of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles with Copper Oxide Co-Catalyst for Photocatalytic Degradation of 2,4-Dichlorophenoxya-cetic Acid. Malaysian Journal of Analytical Sciences, 20, 171-178.

https://doi.org/10.17576/mjas-2016-2001-18 - 4. Reddy, P.A.K., Reddy, P.V.L., Kwon, E., Kim, K.-H., Akter, T. and Kalagara, S. (2016) Recent Advances in Photocatalytic Treatment of Pollutants in Aqueous Media. Environment International, 91, 94-103.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.012 - 5. Ozawa, K., et al. (2014) Electron–Hole Recombination Time at TiO2 Single-Crystal Surfaces: Influence of Surface Band Bending. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 5, 1953-1957.

https://doi.org/10.1021/jz500770c - 6. Shao, M., Ning, F., Zhao, J., Wei, M., Evans, D.G. and Duan, X. (2012) Preparation of Fe3O4@SiO2@Layered Double Hydroxide Core-Shell Microspheres for Magnetic Separation of Proteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 134, 1071-1077.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ja2086323 - 7. Liu, Z., Bai, H. and Sun, D.D. (2011) Facile Fabrication of Porous Chitosan/TiO2/Fe3O4 Microspheres with Multifunction for Water Purifications. New Journal of Chemistry, 35, 137-140.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C0NJ00593B - 8. Alzahrani, E. (2014) Fabrication and Characterisation of Chitosan-Magnetic Nanoparticles and Its Application for Protein Extraction. International Journal of Advanced Scientific and Technical Research, 4, 755-766.

- 9. Wu, W., Wu, Z., Yu, T., Jiang, C. and Kim, W.-S. (2015) Recent Progress on Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Surface Functional Strategies and Biomedical Applications. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials, 16, Article ID: 023501.

https://doi.org/10.1088/1468-6996/16/2/023501 - 10. Zhou, Q., Li, J., Wang, M. and Zhao, D. (2016) Iron-Based Magnetic Nanomaterials and Their Environmental Applications. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 46, 783-826.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10643389.2016.1160815 - 11. Wang, R., Wang, X., Xi, X., Hu, R. and Jiang, G. (2012) Preparation and Photocatalytic Activity of Magnetic Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Composites. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, 2012, Article ID: 409379.

- 12. Li, S., Liang, W., Zheng, F., Zhou, H., Lin, X. and Cai, J. (2016) Lysine Surface Modified Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2 Microspheres-Based Preconcentration and Photocatalysis for in Situ Selective Determination of Nanomolar Dissolved Organic and Inorganic Phosphorus in Seawater. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 224, 48-54.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2015.10.016 - 13. You, L.-J., et al. (2012) Ultrafast Hydrothermal Synthesis of High Quality Magnetic Core Phenol-Formaldehyde Shell Composite Microspheres Using the Microwave Method. Langmuir, 28, 10565-10572.

https://doi.org/10.1021/la3023562 - 14. Chen, F., et al. (2014) Fabrication of Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2 Nanoparticles Supported by Graphene Oxide Sheets for the Repeated Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation of Rhodamine B under UV Irradiation. Dalton Transactions, 43, 13537-13544.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C4DT01702A - 15. Mohammad Alavi Nikje, M. and Vakili, M. (2015) Engineered Magnetic Core-Shell Structures. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 21, 5312-5323.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612821666150917093352 - 16. Huang, X., Wang, G., Yang, M., Guo, W. and Gao, H. (2011) Synthesis of Polyaniline-Modified Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Composite Microspheres and Their Photocatalytic Application. Materials Letters, 65, 2887-2890.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2011.06.005 - 17. Yuan, Q., Li, N., Geng, W., Chi, Y. and Li, X. (2012) Preparation of Magnetically Recoverable Fe3O4@SiO2@meso-TiO2 Nanocomposites with Enhanced Photocatalytic Ability. Materials Research Bulletin, 47, 2396-2402.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2012.05.031 - 18. Fan, Y., Ma, C., Li, W. and Yin, Y. (2012) Synthesis and Properties of Fe3O4/SiO2/ TiO2 Nanocomposites by Hydrothermal Synthetic Method. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, 15, 582-585.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2012.04.013 - 19. Li, J., et al. (2014) Photocatalytic Property of Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Core-Shell Nanoparticle with Different Functional Layer Thicknesses. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2014, Article ID: 986809.

- 20. Alzahrani, E. (2015) Photodegradation of Eosin Y Using Silver-Doped Magnetic Nanoparticles. International Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 2015, Article ID: 797606.

- 21. Yang, W., Liu, X., Li, D., Fan, L. and Li, Y. (2015) Aggregation-Induced Preparation of Ultrastable Zinc Sulfide Colloidal Nanospheres and Their Photocatalytic Degradation of Multiple Organic Dyes. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 17, 14532-14541.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C5CP01831E - 22. Rokhsat, E. and Akhavan, O. (2016) Improving the Photocatalytic Activity of Graphene Oxide/ZnO Nanorod Films by UV Irradiation. Applied Surface Science, 371, 590-595.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.02.222 - 23. Fu, X., Yang, H., Sun, H., Lu, G. and Wu, J. (2016) The Multiple Roles of Ethylenediamine Modification at TiO2/Activated Carbon in Determining Adsorption and Visible-Light-Driven Photoreduction of Aqueous Cr (VI). Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 662, 165-172.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.12.019 - 24. Salehi, M., Hashemipour, H. and Mirzaee, M. (2012) Experimental Study of Influencing Factors and Kinetics in Catalytic Removal of Methylene Blue with TiO2 Nanopowder. American Journal of Environmental Engineering, 2, 1-7.

https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ajee.20120201.01 - 25. Jassal, V., Shanker, U. and Kaith, B. (2016) Aegle Marmelos Mediated Green Synthesis of Different Nanostructured Metal Hexacyanoferrates: Activity against Photodegradation of Harmful Organic Dyes. Scientifica, 2016, Article ID: 2715026.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2715026 - 26. Chaudhari, P., Chaudhari, V. and Mishra, S. (2016) Low Temperature Synthesis of Mixed Phase Titania Nanoparticles with High Yield, Its Mechanism and Enhanced Photoactivity. Materials Research, 19, 446-450.

https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-5373-MR-2015-0692 - 27. Mizutani, N., Iwasaki, T. and Watano, S. (2015) Response Surface Methodology Study on Magnetite Nanoparticle Formation under Hydrothermal Conditions. Nanomaterials and Nanotechnology, 5, 1-7.

https://doi.org/10.5772/60649 - 28. Zheng, B., Zhang, M., Xiao, D., Jin, Y. and Choi, M.M.F. (2010) Fast Microwave Synthesis of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4/Ag Magnetic Nanoparticles Using Fe2+ as Precursor. Inorganic Materials, 46, 1106-1111.

https://doi.org/10.1134/S0020168510100146 - 29. De Matteis, L., et al. (2014) Influence of a Silica Interlayer on the Structural and Magnetic Properties of Sol-Gel TiO2-Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles. Langmuir, 30, 5238-5247.

https://doi.org/10.1021/la500423e - 30. Cui, B., Peng, H., Xia, H., Guo, X. and Guo, H. (2013) Magnetically Recoverable Core–Shell Nanocomposites γ-Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2-Ag with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity and Antibacterial Activity. Separation and Purification Technology, 103, 251-257.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seppur.2012.10.008 - 31. Xue, C., et al. (2013) High Photocatalytic Activity of Fe3O4-SiO2-TiO2 Functional Particles with Core-Shell Structure. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2013, Article ID: 762423.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/762423 - 32. Wang, Z., Shen, L. and Zhu, S. (2012) Synthesis of Core-Shell Fe3O4@SiO2@TiO2 Microspheres and Their Application as Recyclable Photocatalysts. International Journal of Photoenergy, 2012, Article ID: 202519.

- 33. Ahangaran, F., Hassanzadeh, A. and Nouri, S. (2013) Surface Modification of Fe3O4@SiO2 Microsphere by Silane Coupling Agent. International Nano Letters, 3, 23.

https://doi.org/10.1186/2228-5326-3-23 - 34. Kim, J. and Lim, H. (2013) Separation of Selenite from Inorganic Selenium Ions using TiO2 Magnetic Nanoparticles. Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society, 34, 3362-3366.

https://doi.org/10.5012/bkcs.2013.34.11.3362 - 35. Caruntu, D., et al. (2004) Synthesis of Variable-Sized Nanocrystals of Fe3O4 with High Surface Reactivity. Chemistry of Materials, 16, 5527-5534.

https://doi.org/10.1021/cm0487977 - 36. Gao, G., et al. (2010) Shape-Controlled Synthesis and Magnetic Properties of Monodisperse Fe3O4 Nanocubes. Crystal Growth & Design, 10, 2888-2894.

https://doi.org/10.1021/cg900920q - 37. Zhang, Y.-X., et al. (2011) Ultra High Adsorption Capacity of Fried Egg Jellyfish-Like γ-AlOOH (Boehmite) SiO2/Fe3O4 Porous Magnetic Microspheres for Aqueous Pb (II) Removal. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 21, 16550-16557.

https://doi.org/10.1039/c1jm12196k - 38. Yu, J., Yu, X., Huang, B., Zhang, X. and Dai, Y. (2009) Hydrothermal Synthesis and Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity of Novel Cage-Like Ferric Oxide Hollow Spheres. Crystal Growth and Design, 9, 1474-1480.

https://doi.org/10.1021/cg800941d - 39. Yu, J., Zhang, L., Cheng, B. and Su, Y. (2007) Hydrothermal Preparation and Photocatalytic Activity of Hierarchically Sponge-Like Macro-/Mesoporous Titania. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C, 111, 10582-10589.

https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0707889 - 40. Cui, W.W., Tang, D.Y. and Gong, Z.L. (2013) Electrospun Poly (Vinylidene Fluoride)/Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) Grafted TiO2 Composite Nanofibrous Membrane as Polymer Electrolyte for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Journal of Power Sources, 223, 206-213.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2012.09.049 - 41. Jung, K.Y. and Park, S.B. (2000) Enhanced Photoactivity of Silica-Embedded Titania Particles Prepared by Sol-Gel Process for the Decomposition of Trichloroethylene. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 25, 249-256.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0926-3373(99)00134-4 - 42. Ding, Z., Lu, G. and Greenfield, P. (2000) Role of the Crystallite Phase of TiO2 in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis for Phenol Oxidation in Water. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B, 104, 4815-4820.

https://doi.org/10.1021/jp993819b - 43. Chen, J., Wang, Y.G., Li, Z.Q., Wang, C., Li, J.F. and Gu, Y.J. (2009) Synthesis and Characterization of Magnetic Nanocomposites with Fe3O4 Core. Journal of Physics, 152, Article ID: 012041.

- 44. Long, N., et al. (2014) Preparation, Characterization and Photocatalytic Activity under Visible Light of Magnetic N-Dopped TiO2. 3rd World Conference on Applied Sciences, Engineering, and Technology, Kathmandu, 27 September 2014, 670-673.

- 45. Bernhard, A.M., Czekaj, I., Elsener, M. and Kr?cher, O. (2013) Adsorption and Catalytic Thermolysis of Gaseous Urea on Anatase TiO2 Studied by HPLC Analysis, DRIFT Spectroscopy and DFT Calculations. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 134-135, 316-323.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.01.009 - 46. Shinto, H., Aso, Y., Fukasawa, T. and Higashitani, K. (2012) Adhesion of Melanoma Cells to the Surfaces of Microspheres Studied by Atomic Force Microscopy. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 91, 114-121.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfb.2011.10.060 - 47. Yang, H., Wang, Y., Lai, S., An, H., Li, Y. and Chen, F. (2007) Application of Atomic Force Microscopy as a Nanotechnology Tool in Food Science. Journal of Food Science, 72, R65-R75.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00346.x - 48. Ploehn, H.J. and Liu, C. (2006) Quantitative Analysis of Montmorillonite Platelet Size by Atomic Force Microscopy. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 45, 7025-7034.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ie051392r - 49. Haque, E., Jun, J.W. and Jhung, S.H. (2011) Adsorptive Removal of Methyl Orange and Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution with a Metal-Organic Framework Material, Iron Terephthalate (MOF-235). Journal of Hazardous Materials, 185, 507-511.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.09.035 - 50. Yu, L. and Luo, Y.-M. (2014) The Adsorption Mechanism of Anionic and Cationic Dyes by Jerusalem Artichoke Stalk-Based Mesoporous Activated Carbon. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 2, 220-229.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2013.12.016 - 51. Bhattacharjee, A., Ahmaruzzaman, M., Devi, T.B. and Nath, J. (2016) Photodegradation of Methyl Violet 6B and Methylene Blue Using Tin-Oxide Nanoparticles (Synthesized via a Green Route). Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 325, 116-124.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2016.03.032 - 52. Chen, C., Lu, C.S., Chung, Y.C. and Jan, J.L. (2007) UV Light Induced Photodegradation of Malachite Green on TiO2 Nanoparticles. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 141, 520-528.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.07.011 - 53. Al-Qaradawi, S. and Salman, S.R. (2002) Photocatalytic Degradation of Methyl Orange as a Model Compound. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 148, 161-168.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1010-6030(02)00086-2 - 54. Zhou, Q., Zhong, Y.-H., Chen, X., Huang, X.-J. and Wu, Y.-C. (2014) Mesoporous Anatase TiO2/Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites: A Simple Template-Free Synthesis and Their High Photocatalytic Performance. Materials Research Bulletin, 51, 244-250.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2013.12.034 - 55. Cheng, L., et al. (2016) Ternary P25-Graphene-Fe3O4 Nanocomposite as a Magnetically Recyclable Hybrid for Photodegradation of Dyes. Materials Research Bulletin, 73, 77-83.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.materresbull.2015.06.047 - 56. Wang, F. and Zhang, K. (2011) Reduced Graphene Oxide-TiO2 Nanocomposite with High Photocatalystic Activity for the Degradation of Rhodamine B. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical, 345, 101-107.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2011.05.026 - 57. Zhou, K., Zhu, Y., Yang, X., Jiang, X. and Li, C. (2011) Preparation of Graphene-TiO2 Composites with Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. New Journal of Chemistry, 35, 353-359.

https://doi.org/10.1039/C0NJ00623H - 58. Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. and Karimi-Shamsabadi, M. (2013) Decolorization of a Binary Azo Dyes Mixture Using CuO Incorporated Nanozeolite-X as a Heterogeneous Catalyst and Solar Irradiation. Chemical Engineering Journal, 228, 631-641.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2013.05.035 - 59. Es’haghi, Z. and Moeinpour, F. (2014) Surface Modified Nanomagnetite-Assisted Hollow Fiber Solid/Liquid Phase Microextraction for Pre-Concentration and Determination of Palladium in Water Samples by Differential Pulse Voltammetry. Iranian Journal of Analytical Chemistry, 1, 58-64.

- 60. Sahel, K., et al. (2010) Photocatalytic Degradation of a Mixture of Two Anionic Dyes: Procion Red MX-5B and Remazol Black 5 (RB5). Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 212, 107-112.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochem.2010.03.019 - 61. Wang, J., et al. (2009) UV and Solar Light Degradation of Dyes over Mesoporous Crystalline Titanium Dioxides Prepared by Using Commercial Synthetic Dyes as Templates. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 19, 6597-6604.

https://doi.org/10.1039/b901109a - 62. Janus, M., Inagaki, M., Tryba, B., Toyoda, M. and Morawski, A.W. (2006) Carbon-Modified TiO2 Photocatalyst by Ethanol Carbonisation. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 63, 272-276.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2005.10.005 - 63. Sun, H., Bai, Y., Cheng, Y., Jin, W. and Xu, N. (2006) Preparation and Characterization of Visible-Light-Driven Carbon-Sulfur-Codoped TiO2 Photocatalysts. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 45, 4971-4976.

https://doi.org/10.1021/ie060350f - 64. Juang, R.-S., Lin, S.-H. and Hsueh, P.-Y. (2010) Removal of Binary Azo Dyes from Water by UV-Irradiated Degradation in TiO2 Suspensions. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 182, 820-826.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.06.113 - 65. Boumaza, S., et al. (2014) Visible Light Assisted Decolorization of Azo Dyes: Direct Red 16 and Direct Blue 71 in Aqueous Solution on the p-CuFeO2/n-ZnO System. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A: Chemical, 393, 156-165.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcata.2014.06.006 - 66. Jin, Z., et al. (2016) Indium Doped and Carbon Modified P25 Nanocomposites with High Visible-Light Sensitivity for the Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Dyes. Applied Catalysis A: General, 517, 129-140.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2016.02.022 - 67. Ansari, F., Ghaedi, M., Taghdiri, M. and Asfaram, A. (2016) Application of ZnO Nanorods Loaded on Activated Carbon for Ultrasonic Assisted Dyes Removal: Experimental Design and Derivative Spectrophotometry Method. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 33, 197-209.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.05.004

上一篇:Identification, Isolation and 下一篇:Treatment of the High Concentr

最新文章NEWS

- Identification, Isolation and Structure Confirmation of Forced Degradation Products of Sofosbuvir

- Enantiomeric Separation of S-Epichlorohydrin and R-Epichlorohydrin by Capillary Gas Chromatography w

- Characterization of Lignin before and after Exposure to the Gastrointestinal Tract of Ruminants

- Sensitive Determination of Metal Ions in Drinking Water by Capillary Electrophoresis Coupled with Co

- Characterization of Urban Soil with SEM-EDX

- Alterations in Low-Z Elements Distribution in Heart Tissue after Treatments to Breast Cancer Using L

- Multivariate Optimization of Volatile Compounds Extraction in Chardonnay Wine by Headspace-Solid Pha

- Research of Anti-Cancer Components in Traditional Chinese Medicine on Hollow Fibre Cell Fishing and

推荐期刊Tui Jian

- Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine

- Journal of Genetics and Genomics

- Journal of Bionic Engineering

- Pedosphere

- Chinese Journal of Structural Chemistry

- Nuclear Science and Techniques

- 《传媒》

- 《中学生报》教研周刊

热点文章HOT

- Derivative Spectrophotometric and Isocratic High Performance Liquid Chromatographic Methods for Simu

- Volatile Organic Compounds in Crude Coconut and Petroleum Oils in Nigeria

- A Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR) Investigation of NaCl-Induced Phase Separation of Aceto

- An Application of Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) Fast Automated Scan/SIM Type (FASST)

- Characterization of Cellulosic Fibers by FTIR Spectroscopy for Their Further Implementation to Build

- Photodegradation of Binary Azo Dyes Using Core-Shell Fe3O4/SiO2/TiO2 Nanospheres

- Preliminary Phytochemical Content and Antidiabetic Potential Investigations of Panda oleosa (Pierre)

- A Comparative Study of Heavy Metal Concentration in Different Layers of Tannery Vicinity Soil and Ne