Managing the Urban Environment of Manila

Vol.06No.03(2016), Article ID:64382,33 pages

10.4236/aasoci.2016.63010

David J. Edelman

School of Planning, College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 27 January 2016; accepted 7 March 2016; published 10 March 2016

ABSTRACT

This article brings the contemporary thinking and practice of Urban Environmental Management (UEM) to the solution of real problems in a major city of a developing country in Southeast Asia. Such cities confront more pressing problems than those in the developed world and have fewer resources to deal with them. The study first considers urban issues, poverty alleviation, industry, transportation, energy, water, sewage and sanitation, and finance, and then proposes a 5-year plan to help solve the urban environmental problems of Metro Manila, the Philippines, an environmentally complex, sprawling metropolitan region with over 24 million inhabitants.

Keywords:

Urban Environmental Management, Regional Planning, Developing Countries, Metro Manila

1. Introduction

This article focuses on the practice of Urban Environmental Management (UEM) in developing countries, which both face more immediate problems than the developed world and have fewer resources to deal with them. The study is the report of a graduate level workshop that took place at the School of Planning, College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning, University of Cincinnati, USA from August through December 2015. The objective of the workshop was to prepare students to work overseas in data-poor environments as professional consulting planners. Several lectures were given to set the framework for the class of 15 students to operate in sector-level teams (poverty alleviation, industry, transportation, energy, water, sewage and sanitation, finance) preparing a 5-year plan to help solve the urban environmental problems of Metro Manila, the Philippines, an environmentally complex, sprawling metropolitan region in Southeast Asia with over 24 million inhabitants (Demographia, 2015) , utilizing a real-world data base and a limited budget. This project formed the majority of class work culminating in the completion of a professional quality document.

As urban environments increasingly become a central issue in the twenty-first century, compounded by rapid urbanization and climate change, the adoption of urban environmental management initiatives is crucial. That is because urban environmental management provides a framework to mainstream a multitude of issues confronting urban areas through urban planning and development. Different instruments related to the process, planning and management of urban environmental challenges can help cities to promote urban environmental management. The success of these instruments, in addition to other interventions, will prove whether progress is being made in preventing, mitigating, and managing urban environmental challenges (Cities Alliance, 2007) .

Urban environmental management provides a framework to promote sustainable urban environments. As indicated earlier, urban areas throughout history have been centers of prosperity and at the same time of concentrated poverty. With more than half of the world’s population now living in urban areas, and with projections of 70% by 2050 (United Nations Population Fund, 2007), urban environmental management will remain relevant and crucial for managing urban environmental challenges. This is all the more so as urban areas remain critical to promote sustainable development in the 21st century. Urban areas occupy only 2% of the world’s land area; yet they are responsible for the consumption of over 75% of the Earth’s resources. Thay also produce 75% of the total waste generated globally (Girardet, 1999; Desai and Riddlestone, 2002) . Urban environmental problems are “wicked” (Webber, 1973) and require imminent action (Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution, 2007) . With rapid urbanization and climate change, it is apparent that urban challenges will become even more severe if action is not taken now.

Like many developing countries, the Philippines are experiencing rapid urbanization. This is accompanied by several challenges that require managing its urban environment. Moreover, this rapid urbanization has not generated the accompanying prosperity that characterizes countries like China, India, Thailand and Vietnam (Steele, 2014) . Rather, the Philippines is facing issues with poverty, transportation, industry, sewage and sanitation, water supply and financing urban development as the country grows and urbanizes. At the national and local levels, different efforts have been attempted to manage these urban environmental difficulties; yet the urban challenges remain daunting.

2. Poverty Alleviation

In creating an environmental plan for an urban area, especially in a developing country, it is important to consider all the actors in the city and how they use their environment. Often, low-income city dwellers are underrepresented in plans and city institutions. However, it would be remiss not to consider this population in Metro Manila as 3.9% of Metro Manila’s population is considered to be living in poverty (The Borgen Project, 2013) . Since the late 1980s, the Philippines have experienced rapid population growth and slow per capita economic growth, although the latter has increased much more rapidly in recent years. These factors, combined with ineffective trickle-down economic policies and the lack of robust social programs to address the poor, have led to high levels of income inequality (Buentjen, 2011) . This disparity is seen blatantly in Metro Manila.

In order to address this disparity, the National Economic and Development Authority of the Philippines created the Philippine Development Plan 2011-2016 in 2011. The plan’s priorities lie in inclusive economic growth and improvements in government transparency (NEDA, 2011) . This plan, known as the government’s social contract with the Filipino people, sets a vision for development and poverty alleviation programming in the whole of the country. While powerful in creating a unified message, the plan does little to hone in on specific issues of urban poverty in Metro Manila and, therefore, has not created sustainable programs to address the inequality. In Metro Manila, three priority problem areas were identified by the poverty alleviation team: housing conditions in the informal settlements, access to clean water, and lack of job security in the informal sector. These are treated in order below.

2.1. Problem: Housing Conditions in Informal Settlements

Philippine urbanization has a distinct hierarchy of settlements. The Metro Manila landscape is characterized by high rises of moderate and high income citizens and the informal slum settlements of those citizens living in poverty. The settlement hierarchy is very evident with a high concentration of population in a few urban centers.

Deprivation in Metro Manila is income-based, as noted, and infrastructure-based. The region has been unprepared for the rapid rate and high level of urbanization that have exerted tremendous pressure on the megacity’s infrastructure and basic services. This lack of access to infrastructure and basic services has led to the growth of unregulated settlements or slums. The Philippine government has tolerated the growth of slums since the housing market has not been able to keep pace with urban housing demand, especially in Metro Manila (World Bank, 2011) .

Metro Manila, like other megacities in developing countries, has been experiencing rapid urban growth, high population densities, increasing poverty and an escalation of land prices. These forces have led to a critical shortage of affordable land for housing, leaving the majority of the urban poor to live under a constant threat of eviction in unauthorized settlements (Porio, 2011) . These forces have largely contributed to the proliferation of urban poor communities in the metropolis. Tenure insecurity creates cycles of vulnerability, which are magnified in settlements prone to natural disasters.

2.2. Solution: Land Titling for Slum Dwelling Security

This project would be in partnership with USAID, the US Agency for International Development. USAID has been able to implement a similar project in Tanzania that kicked off in 2014. This approach uses mobile technology for land mapping. The “app” approach combines relatively inexpensive and readily available mobile technologies (e.g., GPS/GNSS-enabled smart phones and tablets) with broadly participatory crowd-sourced data collection methods in underserved settings. The approach would train local community members to use technology developed for this purpose to gather land rights and tenure information (USAID, 2014) .

An application with the ability to run on any smart device would be developed with the aim of creating a participatory approach for capturing land rights information, as well as providing a low cost methodology for quickly building a reliable database of land rights claims. A smart phone or handset device would be needed for the mapping. Land tenure is a major issue in Metro Manila; therefore, it would be important for informal settlement dwellers to be educated on the importance of land titling, rather than staying in poor and unstable conditions.

This application might be particularly helpful to the Government of the Philippines as an alternative to more traditional, and costlier, land administration interventions. Formal land administration systems in the Philippines have generally not met the need for accessible, cost effective and appropriately nuanced land registration. As a result, large majorities of informal settlements live without formalized rights to land and other valuable resources. This lack of documentation constrains the ability of individuals and communities to develop a sense of belonging, resulting in deprived accommodation and social instabilities among poor citizens in Metro Manila. Thus, this app would increase land tenure security for slum dwellers.

2.3. Problem: Inadequate Housing and Slum Proliferation

The major issue with poor housing and slums is related to the growing number of urban residents and how housing and infrastructure services can be financed for future urban generations. Upgrading housing and slums can be complex and unclear, because several interrelated components, including physical and social environments, must be addressed that entail significantly different financial consequences: a) infrastructure components like housing, water, sanitation, roads and footpaths, storm water drainage, lighting or public phones; b) service components like waste collection, schools, medical centers and, c) other services such as community buildings, public spaces, and peace building and poverty reduction programs. Informal settlements are unplanned, densely populated, and neglected parts of cities where living conditions are extremely poor (Sticzay, 2015) . Much of the housing stock in these informal settlements is inadequate and unsafe; therefore, physical improvements to housing are needed, in partnership with community building. The process of slum upgrading involves the improvement of both physical and social environments. Projects show that tri-sector partnerships, including the state, private and nonprofit sectors, have to cooperate in order to manage effectively a slum upgrading program. Even though the enumerated parties show commitment, the urgent needs of individual slum dwellers and local communities also have to be considered. In order to make slum upgrading successful in the long term, enduring and strategic planning must be addressed in all financial, institutional and regulatory decisions (Programa Vivenda, 2015) .

Living in bad environments deprives people of a quality of life enabling them to have better incomes and gainful employment. In particular, poor environments lower the physical and mental health of households, which adversely affects productivity, lowers the performance of children in schools and increases vulnerability to crime and violence (World Bank Annual Report, 2011) . As relocation is not always the favored alternative, slum upgrading and improving the informal housing stock represent viable approaches. That is especially true when considering that poor families living in Metro Manila often use their own savings, as well as their own labor, for the construction and refurbishment of their houses. Nevertheless, poor families need to be enabled to help themselves.

2.4. Solution: Slum Upgrading Program

The project proposed here, the Slum Upgrading Project (SUP), is an initiative of private investors, international aid organizations, and local authorities with the aim of creating small offices that would be in-stalled in the informal settlement areas. Slum upgrading projects are very popular in São Paulo, Brazil. Projects like “Programa Vivenda” have already helped around 100 informal settlements across the deprived areas of the city with the refurbishment of units according to their necessity and priority. With economic support and an affordable payback period, this is an excellent alternative for the slum dwellers of Metro Manila to improve their living conditions. These offices would offer to the community credit line facilitation with a maximum cap of $5000 per household to upgrade living conditions, with a payback expectation of 10 years. The office units would consist of a team of young architects, engineers and professionals in the construction field, who would execute the upgrading quickly and effectively in the informal settlements. At the same time, training for the participants would be offered to improve construction techniques and generate economic growth inside the informal settlement areas.

The offices would be built of sustainable materials in a strategic location that would be easily accessible to the participants. In the office, there would be one architect and one engineer, who would lead the office, with two assistants and one administrative person. The project would focus on the areas of the Metro Manila with the highest number of informal settlements. Offices would be built in the following cities: Pasay City, City of Muntinlupa and Mandaluyong City (Nakamura, 2009) . The implementation of the project would take ten years with the objective of building five offices that would assist and support the local community.

2.5. Problem: Limited Access to Clean Water

People living in slums have limited access to potable water for a variety of reasons, including poor infra-struc- ture and polluted water sources. In order to meet basic needs of the slum dwellers and prevent water-borne illnesses, it is important to provide a low-cost option to allow them access to clean water.

2.6. Solution: Clay Water Filters for Clean Water Access

Providing water infrastructure to informal settlements faces many challenges and is very expensive. In order provide a quick solution to the problem at hand and prevent illness, providing filters as a way to treat water is the best route. A US-based non-profit called Potters for Peace has pioneered a model of making and distributing low-cost ceramic clay water filters. They reject the “hand-out” model and in-stead opt to engage community members. They assist communities in making small production and distribution facilities. The Potters for Peace model is so successfully because it not only provides a means to get clean water, but it also provides economic development for neighborhoods. Using locally sourced clay, and training community members to construct the water filters, ensures that it is a low-cost and sustainable method. These clay filters have been used widely throughout South America and other parts of the developing world. Collaboration with Potters for Peace would be necessary in implementing this project, as it would provide the support and knowledge to develop and establish this project in the Philip-pines.

2.7. Problem: Poverty and the Informal Sector

A survey to identify citizens’ pressing concerns in Metro Manila found that low-income residents identified lack of job security and insufficient financial resources as top concerns (Illy, 1986) . Lack of job security and lack of access to capital are rampant among low-income populations, many of whom participate in the informal work sector. In depressed settlements, 16% define their work status as unregistered, 18.6% consider themselves part of the informal economy, 39% are unemployed and 16.7% work part-time (Ragragio, 2003) . Many poor individuals fluctuate between various job statuses. The informal sector consists of, but is not limited to, vending, domestic housework, construction work, handcrafting and self-employment. Throughout the past few decades, street vendors have been viewed as a menace to the urban landscape by the government. Historically, government programs focused on relocating and criminalizing informal sector workers, rather than addressing the problem through structural changes (Illy, 1986) . In recent years, the government has passed legislation, such as the “ Magna Carta for Workers in the Informal Economy (2013) ” and House Bill 968, “ An Act Providing for the Security and Protection of Vendors in the Workplace and for Other Purposes (2012) ” that have, in theory, provided for the security of informal sector workers. These acts provided guidance on including the informal sector in the policy formation process on the local government level; however, they have not been adopted by many local governmental units (LGUs). To ensure job security in the informal sector, policies created at the national level need to be implemented at the local government level. In order to have these policies enacted by LGUs, advocacy efforts are needed. There is a great representational gap that exists among participants in the informal economy. Due to this gap, it is difficult for the informal sector workers to advocate for their protection, for access to capital, for training programs and for other social services (Ragragio, 2003) .

2.8. Solution: Department of Labor and Employment Program for Informal Sector Workers: An Evaluation and Plan

The verbiage surrounding the informal work sector has improved considerably during the last decade with legislation such as the “ Magna Carta for Workers in the Informal Economy (2013) ” and House Bill 968, “ An Act Providing for the Security and Protection of Vendors in the Workplace and for Other Pur-poses (2012) .” However, this legislation has had little effect on the ground.

The Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) has been a key participant in designing initiatives to support the informal economy and protect workers (Casanova-Dorotan et al., 2010) . In 2007, DOLE, in partnership with the local governmental units (LGUs), UNDP and the International Labor Organization (ILO), implemented Unlad Kabuhayan Programme Laban saKahirapan (DOLE, 2007) . The Worktrep program aimed to bring together members of the informal economy and representatives from LGUs to collaborate and improve the socio-economic status of the informal sector (IS) workers. Worktrep is an acronym for “Work-entrepreneur.” DOLE relies heavily on LGUs as the program implementing partners. In order to attract and train them to participate in the Worktreps program, DOLE provides capability-building training and an orientation to introduce the LGU workers to the program.

The LGUs are tasked with implementing four primary services, according to DOLE: 1) training services that cover production and business management skills, as well as occupational safety, preventive health practices and confidence building; 2) assistance to allow IS workers to access the market, credit and technology; 3) access to the government’s insurance schemes for health and social protections; and 4) the provision of networking services allowing IS workers to obtain representation in government and create linkages with private sector partners (Ibid.).

The Worktrep program is a novel initiative that focuses on two important aspects of engaging the informal sector workers: capacity and financial skills building and ability to organize, advocate, and work with the LGUs. While the program was introduced in 2007, there is little literature on the success, challenges or outcomes of the implementation. With that fact in mind, a program evaluation is necessary to study the outcomes and determine the direction of the program going forth.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee established Principles for Evaluation of Development Assistance (OECD, 2015) . These principles guide an evaluation process of development programs and include themes such as relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability. Each theme contains guiding questions to use in the investigation. In order to implement this project, an outside strategic planning and evaluation consulting firm would be hired by DOLE. Using an outside firm would increase transparency and ensure unbiased results. Once the program evaluation is complete, employees at DOLE and representatives from all of the LGUs should work to identify any major changes needed to make the program more effective to implement further as the second edition of Worktreps. It is anticipated that the evaluation process would take approximately one to one and a half years. The strategic analysis and planning for the second edition of Worktreps would take one year, and would be followed by a pilot project and then full implementation.

2.9. Problem: Gender and the Informal Sector

Women constitute over half of the informal economy in Metro Manila (Frianeza, 2012) . It has been stressed in recent years that women’s full participation in all aspects of life―economic, political, and otherwise―is key for the successful development of a country. Women are often relegated to the informal economy due to cultural constructs that require them to complete household responsibilities and stifle their chances of obtaining a high level of education. As a result, the informal economy provides an opportunity for women to work around their family obligations in low-skill jobs (Moser and McIlwaine, 1997) . Many of these women take advantage of their situation by establishing home-based enterprises as well. However, they are the most vulnerable population within the informal sector economy, and many lack the ability to access credit or start-up capital (Bonnin, 2004) .

2.10. Solution: Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs) for Women’s Economic Empowerment

Women in the informal economy face challenges and unequal opportunity, leaving them more vulnerable than their male counterparts. Based on this knowledge, it is critical that Metro Manila focus on engaging women in the informal sector work force and providing them with the financial and social capital to participate actively in the sector, advocate for themselves and learn additional skills. Microfinance institutions have been operating around the world, providing low interest loans to low and moderate income individuals. This model has been very successful, as is evident with the Grameen Foundation, which has worked extensively in Bangladesh, India and other developing countries around the world to bring people out of poverty (Grameen Foundation, 2013) . However, many microfinance institutions (MFIs) are more suited to catering to those individuals who already own small businesses and those who have basic education and knowledge about lending. MFIs also only provide credit to their clients, whereas many poor people need access to more than just credit; i.e., they need to have the ability to save (VSL Associates, 2015) .

A new model of microfinance that includes this savings component was pioneered by the international non-profit CARE in 2000. This model is known as the Village Savings and Loans Association program or VSLA, for short (Hendricks, 2011) . The VSLA model was created to fill the gap between services being offered by microfinance institutions and the very poor. Through creating groups of VSLAs, poor people have access to save a minimal amount each week and then apply for loans from the association's bank. Lauren Hendricks, the Executive Director of Access Africa, a CARE Initiative, explains that VSLA participants saved 10 cents each week and were able to borrow $5. In the second year, the participants would have worked up to saving around $1 to $2 a week with the ability to borrow $30 to $40 (Ibid.). In that sense, the VSLAs provide a launching platform for individuals to start saving and receiving loans to prepare them for a formalized microfinance system in a year or two. As a result, VLSAs are a strong approach to engaging women in the informal economy and empowering them socially and economically.

3. Industry

3.1. Existing Economic Conditions

For most of its history, agriculture has been the main industry in the Philippines, and this is true in all seventeen regions of the country. After food products and food processing, mining is the second major industry. With regard to manufacturing, electronics are the most exported, but also the most imported, products in the country. In December 2014, 49.5% of the total exports of the month were from this sector. Minerals and machinery are other major imports of the country (Economy of the Philippines, 2015) .

Between 1960 and 2012, the Philippines experienced a steady decline in the share of agriculture in total output and employment. “In other developing countries, the decline in the share of agriculture is typical-ly picked up by the industrial sector. In the case of the Philippines, this was picked up by the services sector.” According to the CIA’s World Factbook (2015) , in 2011, more than half of the economy was based on the services sector. The agriculture sector had 33% and the manufacturing sector had a 15% share. In 2012, services accounted for 57.1% of GDP, compared to 31.1% for industry and 11.8% for agriculture. In the same year, 52.5% of the labor force was employed in services, 15.4% in industry, and 32.2% in agriculture. The importance of the services sector is also reflected in the external (balance of payments) accounts of the Philippines, which show a deficit on the trade in goods account and a surplus on the trade in services account (Lee, 2014) .

The Philippine government provides incentives for private institutions to encourage public-private partnerships for financing construction, operation and maintenance of public infrastructure, and development projects. Despite the restrictions that the country’s 1987 Constitution and other laws set for foreign ownership, the government is encouraging foreign interests to “invest in the country with the businesses that improve employment opportunities, develop productivity of the sources, heighten the value and volume of the exports and provide opportunities for the future developments in the economy (CIA, 2015).” The top trading partners of the Philippines are Japan, the US, China, Hong Kong and Singapore (Philippines, 2015). Since the Philippines is experiencing growth in some of its industrial sectors and turning into an investment hub for the region, there are multiple stakeholders, development companies and banks from these countries that are willing to invest in Philippine industry.

Metro Manila, as the capital of the country, is the most significant metropolitan region in the Philippines. Due to the very centralized economy of the country, most of the businesses and major companies are located here. This investment focus on Metro Manila provides the NCR with most of the country’s infrastructure required by businesses and, therefore, reduces the cost of doing business there. Compared to the rest of the country, Metro Manila has a lower percentage of manufacturing and higher percentages of tourism, business, finance and transportation in its shares of output by industry. The trade and tourism industry, with a 31.4% share, is the most important industry of the NCR. Business and finance, with 28.6%, and local/non-market, with 15.6% follow (Economy of the Philippines, 2015) .

With the above mentioned strengths and opportunities that the Philippines have for industrial investment, there are some weakness and threats in this sector as well. “The Executive Opinion survey, conducted annually by the World Economic Forum, considered corruption as the most severe impediment to business in the country in 2014 (17.6% of respondents), followed by inadequate infrastructure supply (15.9%), tax regulations (13.3%) and inefficient government bureaucracy (12.6%).” From the environmental view, pollution, especially in the largest cities such as Metro Manila, is the main problem of Philippine industry. Unemployment and population growth are other major issues. Metro Manila is the city with the densest population, and a considerable number of people seek better job opportunities in the capital. However, employment in the NCR has increased by only 5% from 2009 to 2014 (Brookings Institution, 2015) .

3.2. Economic Outlook

Due to the constant recent increases in private consumption, improvement in exports and a stable in-vestment climate in the Philippines, the country’s economy has expanded. With a lower employment rate, modest inflation and overseas Philippine remittances, there has been growth in GDP. The average annual rate of growth is 1% and is projected to grow by more than 4% per year over the long-term based on projections of the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) of the Philippines. However, this strong GDP increase is assumes a fixed annual population growth rate of 1.89% (NEDA, 2014).

The economy of the Philippines is doing quite well when compared to its neighbors. Indonesia, with an annual GDP growth rate of 6.3%, is the only one experiencing better progress. Malaysia’s growth is at a rate much the same as the Philippines, and Thailand, with a 2.4% annual increase in GDP, is growing more slowly (Oxford Business Group, 2015) . The industry and services sectors, like the other parts of the economy, are continuing to grow. However, this growth needs to be sustained. The international market for the Philippines in the rapidly growing economy of East Asia is a key point in its improvement. Innovation in industry and services with the creation of new products linking different sectors, as well as optimizing productivity, innovative strategies and policies are some factors that can have a great impact in the growth of these sectors (NEDA, 2014).

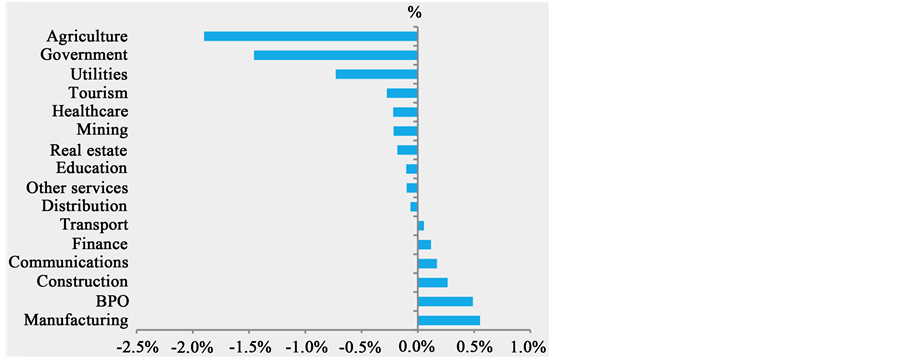

There is evidence to support the statement that, “of all sectors, the (Business Process Outsourcing) BPO industry tops the list for size and growth trajectory, providing employment opportunities and encouraging foreign investments into the country ( Manila Bulletin, 2015 ; also see Figure 1).” This follows the shift to service based industry in the economy of the country. Currently, there are more than one million employees in BPO and related IT sectors in the Philippines. With the rapid growth of these sectors, the World Bank projects up to $55 billion USD total income by 2020 and the addition of 1.5 million new jobs. Compounded by additional favorable conditions such as a significant skilled young population and lower labor costs compared to the rest of East Asia, there is a positive outlook here, as well as incentives for more investment, and, therefore, growth in these sectors (Romualdez, 2015) . For Filipinos, the higher salaries from working in call centers make these positions desirable, even with the difficulties that may arise because of nighttime working hours and the accompanying necessary changes in lifestyle.

Figure 1. Philippine employment by sector 1980-2012. Source: Oxford Economics/Haver Analytics, 2015.

3.3. The Rise of the Business Process Outsourcing Sector

Business process outsourcing (BPO) involves contracting a third-party provider to execute specific business services such as back-of-office operations. The first BPO call center in the Philippines began serving foreign customers in 1997. It was preceded, and partly made possible by, the deregulation of the telecommunications industry in 1995. The Philippines garnered 6% of the global BPO market in 2007, and it climbed to 10% in 2012 (Deloitte, 2014). The largest BPO customer-base is comprised of companies that are based in the United States, including Accenture ($648.6 million USD) Convergys ($396.6 million USD) and JPMorgan Chase Bank N.A- Philippine Global Service Center ($160.8 million USD) (Newsbytes, 2014) .

The success of this sector in the Philippines can be attributed to the hospitable nature of Filipinos, which translates into excellent customer service; its cultural affinity with the US, which results in the acquaintance with and usage of American English and idioms, and, finally, a highly educated workforce that has the aptitude to function in domains like information technology, finance and animation.

A federal investment of $30.6 million USD over 8 years (2006 to 2014) financed the business skills training for call center employees (Lee, 2014) . In acknowledgement of the dependent relationship between exceptional English skills and the success of BPO endeavors, the government also led an initiative to institute the National Proficiency Exam in order to ensure that teachers are proficient and can instruct those who are potential BPO employees in that language.

The federal government has redirected its support, including funding and marketing efforts, to grow the industry in “Next Wave Cities (NWCs)” such as Baguio City, Davao City and Dumaguete. NWCs are cities located outside of Metro Manila that have experienced significant economic growth and have been identified as having the capacity to sustain and amplify those gains for the overall advancement of the country. This approach reflects the federal government’s strategic priority to disperse wealth and job opportunities beyond the NRC proper. Mature and startup BPO companies alike are gradually relocating due to “the rising cost of rent, manpower, and power-generation (in Manila) (Ibid.)”.

Disinvestment on the part of the federal government is not a sign that the market is cooling in Metro Manila. In fact, as of 2014, Metro Manila has become the second largest destination for companies seeking BPO services. As a proven vehicle for economic success, the position of BPO enterprises in the region’s job creation agenda should be reinforced. Metro Manila is the market leader and, therefore, has the clout and experience to expand the breadth of its BPO services into new categories like health care.

3.4. Priorities

Manila main industrial initiative for the next five years, then, should be to implement the following projects in order to reinforce the city as a BPO:

Establish a call center in Mandaluyong near its network of universities and technical schools;

Offer job training for new and current employees;

Secure Aetna or Anthem as a BPO client;

Perform a study to determine the viability of medical tourism in Manila, and

Develop a superblock in the south to serve as the hub for expansion into health care BPO’s.

4. Transportation

4.1. History and Context

Serving the largest urban population in the country, the Metro Manila transportation system faces the difficult challenge of connecting its 17 local government units (LGU). At present, those connections comprise two LRT lines, one MRT line, an extensive system of local roads and highways for private automobiles, tricycles, jeepneys, buses, bicycles, pedicabs, ferries and pedestrian routes. Road transportation mobilizes 98% of vehicle passenger traffic in the Philippines (Asian Development Bank, 2012) , and its overall dominance in Metro Manila makes it the sector in which changes and improvements will have the greatest impact in the region.

The population and economic growth that Metro Manila has experienced during the last few decades has resulted in accelerated automobile ownership and, with this, increases in congestion (Asian Development Bank, 2012) , pollution (Robles, 2012) and costly commute times. An Asian Development Bank report estimates 4.6% of GDP losses in congestion, (ADB, 2012; Buco and Buco, 2009; Robles, 2012) , and traffic accidents (Flor, n. d.) . As of 2007, the leading form of motor vehicles registered in the country was Motorcycles and Tricycles, which constituted approximately 48% of all registered motorized vehicles, followed by Utility Vehicles (including jeepneys), which were approximately 29%, Automobiles being 14%, Sports Utility Vehicles accounting for 3%, Buses 0.5%, and Trailers accounting for 0.4% of all registered motorized vehicles in the country (Ibid.).

The issues related to motorized vehicles are expected to escalate if a change in the current transportation system does not occur. The Philippines Land Transportation Office reported that the number of vehicle registrations has been growing at a rate of 6% per year (World Bank, 2011) . Furthermore, population growth in Metro Manila over recent decades has been rapidly forming a belt-like corridor surrounding the city center (Murakami and Palijon, 2005) , calling for more efficient, sustainable, and health-conscious means to connect inner-metropolitan populations in a way that does not further threaten public health or cause more degradation to the environment (as the proliferation of subdivision construction is contributing to land degradation and flooding as discussed by Murakami and Palijon, 2005 ).

The focus of the national government for the transportation sector has been influenced by the major decentralization process marking recent decades (Porio, 2012) . This decentralization has resulted in the devolution of power and service-provision from the national government to the local government units (LGUs), which has placed communities closer to their authorities, but also strengthened political elites and corruption. Furthermore, this has left some LGUs unequipped and unprepared to undertake transportation planning roles that require greater (regional) vision, coordination and funding. The weak local management of transportation planning efforts has contributed to deficiencies in the disbursement of infrastructure funds, leaving 44% of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) available budget unused in 2007, despite the substantial demands for projects addressing transportation issues (Asian Development Bank, 2012) .

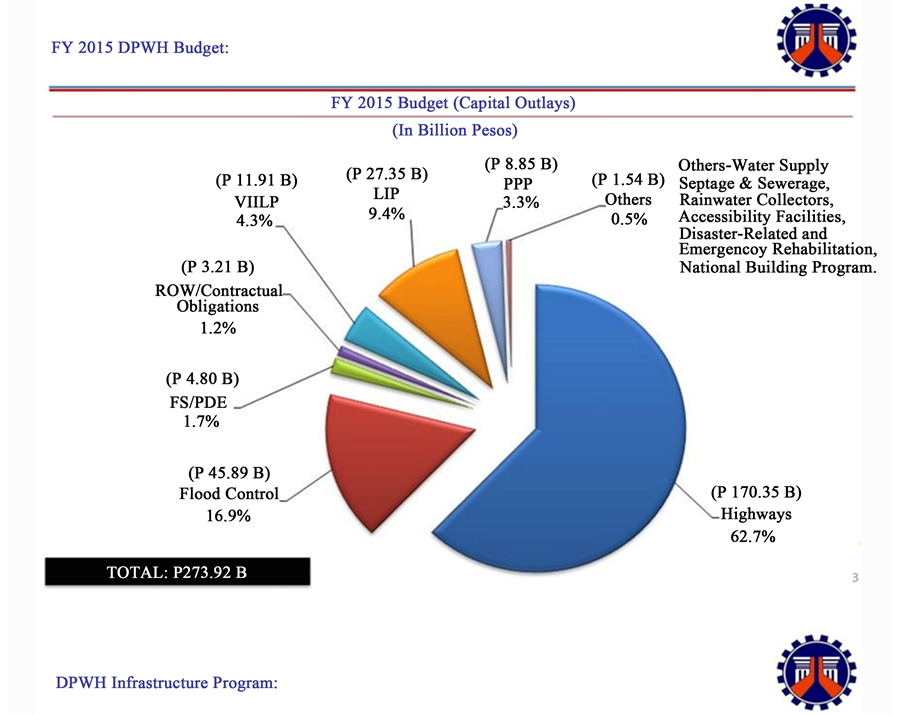

The decentralization process has also placed emphasis on distributing national infrastructure efforts more evenly throughout the archipelago, which has translated into efforts to build more highways and national roads with a goal to pave all national roads by 2016 (Royal Gazette, 2015) . The ambitious undertaking of consolidating a road network linking vast amounts of unconnected land has removed the focus from resolving the complex transportation problems of Metro Manila. This is visible by looking at the regional breakdown of DPWH funds dedicated to infrastructure for fiscal year 2015, which allocated 8.8% of its $4.5 billion USD budget to the National Capital Region as opposed to other regions requiring more complex projects and receiving from 18% to 29.3% of the DPWH funds (DPWH, 2015) (see Figure 2). The reduced presence of national funds and challenged local management of transportation initiatives has resulted in the greater presence of privately-led projects initiated through unsolicited proposals to LGU’s and also via public private partnerships (Asian Development Bank, 2012) . Also, the strong foreign-investment led transportation infrastructure culture that predominated in the Philippines in the 1990’s is still significant (Donaldson et al., 1997) , in addition to foreign aid having been added to the mix of non-national government funding for transportation projects in the region.

The fast population growth, weak, underfunded and disconnected local-level transportation planning, plus the

Figure 2. DPWH chart-shows 63% of DPWH fiscal year funds allocated to highway development. Source: Department of Public Works and Highways, n. d.

disproportionately car-focused transportation vision have left the fastest growing region of the country, Metro Manila, with a transportation system unable to keep up with the demand of its growing population and 3 million daily commuters (Robles, 2012) . Furthermore, the proposed solution by the national government, reflected by the large percentage of spending for highways-63% of the FY 2015 budget as shown in Figure 2, to construct more highways, is a key contributor, rather than a solution to these problems.

The current LRT and MRT lines are positioned to serve mid- and long-distance trips, but are extremely over capacity with more than 450,000 passengers a day utilizing a system designed only for 350,000, even with capacities recently expanded (Railway Gazette International, 2007) . Despite the additions of planned rail extensions for Line 4 and Line 6 of the existing rail system, as well as the Manila-Calabarzon Express line (MCX), the majority of the city’s congestion issues lie in the number of motor vehicles flooding the road infrastructure of the region. Furthermore, the lack of efficient and well defined collective transportation means to cover short- to mid-distance trips results in people taking recourse to unsustainable, inefficient and polluting car or jeepney trips (see Figure 3), or further adding to over-capacity problems in the major rail systems.

4.2. Solutions

Upon analysis of the issues, the transportation proposal consists of three main initiatives.

Short-Term Initiative-Consisting of 5 years, in this phase the focus is on the most prevalent modes of transportation in the region: jeepneys and tricycles. Due to the cultural and economic significance of these vehicles, their general form and function would be preserved, but these vehicles would transition away from diesel engines towards electric models. This would help reduce the nation’s reliance on foreign fuel and have the greatest impact within a short period of time.

Figure 3. Jeepney spotlight. Source: https://quinsprogress.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/jeepney8.jpg , 2014

Mid-Term Initiative-Consisting of 5 years, this phase would consist of an ongoing long-term so-cial program focused on educating young adults, teenagers and children about sustainable means of transportation and encouraging a cycling culture. This would be accomplished through media, school programs and leisure activities. Metro Manila is already experiencing a congestion crisis, and demographic trends show that children and teenagers are the largest demographic population groups. As these large groups reach adulthood, the impact of their prevalent choices for transportation modes will be profoundly meaningful, either further exacerbating the current transportation sector problems to unprecedented levels or helping transition the region into more sustainable transportation networks.

Long-Term Initiative-Consisting of 15 years, in this phase, the creation of inter-LGU non-motorized or low- impact motorized transportation networks to facilitate short trips is proposed. Cycling, e-tricycles, and walk- ing have been selected as the main modes of transportation for these corridors. The plan is to identify existing narrow paths that permeate the urban fabric and which already serve as non-motorized transportation pathways. These corridors display vibrant mixes of uses, and investments formalizing them into green-paths would encourage non-motorized transportation.

This three-pronged strategy aims to address the main issue at stake: the fact that a car-oriented transportation system is a system not realistically sustainable for this region. The infrastructure that is needed to support a car- oriented system, based on extensive, sprawling urban development, is contradictory to the natural landscape of Metro Manila. Continuing current land development patterns is not possible due to the region’s containment by water boundaries. Furthermore, the region is in constant need of natural water-absorption mechanisms to cope with frequent water accumulation events following heavy precipitation patterns of the area. In addition, the densities that Metro Manila exhibits would make it unsustainable for everyone to drive a car. The inefficiencies of the massive demand for parking that this would generate would result in a substantial burden on land that the region cannot accommodate.

5. Energy

5.1. Political Characteristics

MERALCO, Manila’s energy distributor, does not have a good relationship with the public amid several legal battles, accusations of corruption, bribes and money laundering. While MERALCO will finance and operate two brand-new 400-megawatt generators in Jurong Industrial Estate, Singapore (The Manila Times, 2014) , many are wondering why they did not build these plants in the Philippines. MERALCO is profiting from denying an increase in capacity and supply, charging higher and higher prices for electricity (and much more than what is being charged in Singapore); “…something must be terribly wrong here when our biggest utility firm, which controls 60 percent of the electricity market, chooses to invest billions of pesos outside the country, which has been capital-deficient (The Manila Times, 2014) .”

Strain among the different political families also affects the energy industry. In 1986, President Corazon Aquino refused to operate a large nuclear power plant that had been built in Bataan because it was constructed by the Marcos administration (Pascual, 2013) . Officials have said that the reason for closing the plant was its proximity to an inactive volcano and nearby fault line. However, the International Atomic Energy Agency has inspected the plant twice, and cleared it for operation. Although these safety concerns were highlighted, “the plant was built to withstand an Earthquake of an Intensity 8 on the Richter Scale, as well as built at 18 meters above sea level to be sufficiently protected against storm damage like tidal waves and tsunamis (National Power Corporation, 2014) .” The current president, Benigno Aquino III, who is the son of Corazon Aquino, has little interest in reopening the plant.

5.2. Socio-Cultural Characteristics

Socio-cultural characteristics can strongly affect people’s energy consumption behavior. Power struc-tures (relations among people), status and social belonging can help explain certain attitudes toward consumption (Sahakian, 2011) . In Metro Manila, air-conditioning use and private car ownership are very desirable as status symbols. Only the affluent can afford to have air-conditioning or a car, which are both energy intensive. Approximately 67% of people in the Philippines use energy for cooling. However, only 9% of people own air-conditioning, with the vast majority using electric fans (Ibid.). Globalization also affects social perception around energy consumption. Many Filipino return migrants especially see air-conditioning as a status symbol and put units specifically in front of their houses for people to see. In addition, following western fashion trends is important even when it comes to fall and winter clothing. There is also little use of passive or natural ventilation in built spaces because many people want western style architecture. Not only is this type of architecture not appropriate for the climate, but traditional structures are well ventilated and use natural light. While the Philippines has been greatly influenced by the American environmental movement, there has been less consumer activism (Ibid.).

5.3. Physical and Geographical Characteristics

The Philippines is an archipelago of 7107 islands. They are mostly mountainous with varying amounts of coastal lowlands. Metro Manila is in one of these low lying areas between Manila Bay and Laguna de Bay. The total range of elevation in the Philippines is 9700 ft. (2954 m.), while land use is primarily agricultural (41%) and secondarily forest (25.9%) (CIA, 2011).

The climate is tropical and maritime. There are relatively high temperatures throughout the year, high humidity, and large amounts of precipitation. The average annual temperature is approximately 80˚F (26.6˚C). The temperature fluctuates slightly. In January, the coldest month, the average temperature is around 78˚F (25.5˚C), while in the warmest month, May, the average temperature is 83˚F (28.3˚C). The monthly average for relative humidity ranges from 71% to 85% depending on the month. Rainfall is the single most important climatic factor in the Philippines. Depending on the region, the average annual rainfall could be between 38 inches (965 mm) or 160 inches (4064 mm). The Philippines is subject to monsoonal seasons. Therefore, there are two seasons: wet and dry. The wet season occurs from June to November, and the dry occurs from December to May (PAGASA, 2015) .

An important geographical feature of the Philippines is that it is on the “ring of fire.” This causes issues associated with tectonic activity, including earthquakes, volcanic activity and eruptions, lahars (mud flows) and landslides. There are currently 53 active volcanoes throughout the Philippines (VD, 2015). The climate and tectonic activity of the Philippines have allowed it to build extensive hydroelectric and geothermal facilities; hence, their importance to the energy sector.

5.4. Environmental Characteristics

The Philippine Development Plan 2011-2016 includes an Environmental Framework. The framework includes 3 goals: improved conservation, protection and rehabilitation of natural resources; improved environmental quality for a cleaner and healthier environment, and enhanced resilience of natural systems and improved adaptive capacities of human communities to cope with environmental hazards including climate related risks. The second goal is the one that is most connected to energy use in Metro Manila; it includes the measure to “reduce air pollution in Metro Manila and other major urban centers including the promotion and use of clean fuel and indigenous resources to the fullest as sources of clean energy (PDP, 2011).”

Another measure to combat energy related environmental issues is to “develop and replicate low-cost technologies to optimize the recycling, reuse, and recovery of solid waste, including the conversion of residual organic materials into clean renewable energy (Ibid.).” Moreover, “the continually increasing demands for food, energy, and other goods, coupled with rapid development have put much stress on the natural environment resulting in the destabilization of ecosystems, destruction of natural habitats, and an alarming rate of biodiversity loss (Ibid.).”

Metro Manila contains the chief port of the Philippines, Manila Bay, which is rimmed by “heavy industries, refineries, and a power plant in Bataan, while Metro Manila is highly urbanized with light and heavy industries and factories located in various parts of the metropolis (Jacinto, 2006).” Due to rapid development and increased demand, Manila Bay and other urban esteros (estuaries) have been deemed eutrophic and unfit for human activity (PDP, 2011). Industries in the region contribute greatly to air and water pollution, which “significantly contributes to episodic hypoxic conditions in bay waters, toxic algal blooms, and suspended materials in water columns (Jacinto, 2006).” The Pasig River watershed, which divides the NCR into Northern and Southern districts, is highly inhabited and highly polluted. The dumping of wastewater and garbage from industries, households and slums contribute to this. Metro Manila produces 8,000 tons of garbage per day, and only 70% is collected; what is not collected goes into the waterways (PDP, 2011). The cost of medical treatment and loss of income from water-borne diseases totals approximately $141 million USD per year. Traffic congestion and unsustainable fueling methods contribute to about 80% of urban air pollution, air quality issues, and smog. As of 2011, the total suspended particulates in Metro Manila were 166 Mg/Ncm, which was 84% above the standard 90 Mg/Ncm as determined by the World Health Organization (WHO) (Paje, 2011) . Due to the high rate of fossil fuel use, Metro Manila emits high rates of CO2. It is projected that in 2020, the region will emit 23.5 million metric tons from electricity alone (Ajero, 2000) .

This is not accounting for any emissions from transportation, which make up the bulk of carbon emissions. The import of coal and oil for energy use also contributes significantly to environmental difficulties. The transport of coal and oil has contributed to small spills and water pollution, while the actual conversion of the minerals into energy greatly contributes to air pollution, the degradation of landscapes and ecosystems, surface and ground water pollution from combustion waste, sludge, and acid mine drainage, and the obvious and well- known contribution to global warming. Because most energy in Metro Manila is produced from coal, there are serious implications to the environmental sustainability of the region. Potential areas of clean and sustainable energy investment include bio-energy, solar and wind energy, geothermal energy and hydropower.

5.5. Issues

5.5.1. Issues with Public Distrust

Issues of the public’s distrust in the country’s government and sole energy provider, MERALCO, are present and increasing. Growing distrust in the energy sector comes on the heels of the announcement of MERALCO’s involvement in the development of two generators in Singapore, even though MERALCO officials have been quoted as saying Manila’s energy supply problems are due to a lack of generators (The Manila Times, 2014) . There has also been involvement of the provider in lawsuits for suspected money laundering and bribery. Electricity charges (per kWh) often change month to month. Some citizens are quoted as saying “This MERALCO Corporation is run by a bunch of dummies; make that rich dummies,” and “These are the killers of Philippine progress, sabotaging the economy (The Philippine Star, 2015) .” MERALCO has been accused of catering to specific people (those with high economic and/or political standing). This is a problem for low- and middle-income citizens with no money or political pull. Their needs often go ignored, adding to their troubles and disparities, and confirming the corruption that goes on in this sector. In fact, the Philippines ranked 85th out of 175 countries in the Corruption Perception Index in 2014 with a score of 38 out of 100 (0 being highly corrupt and 100 being very clean) (Transparency International, 2014) . The country is improving though; it ranked 94th in 2013.

5.5.2. Issues with Education

The colonization of the Philippines by the United States promoted a high standard for education. Filipi-nos view education as a necessity and an avenue to social and economic mobility, and they exhaust all resources trying to provide adequate and quality education for their children. Access to education in Metro Manila largely depends on economic status. The country as a whole lags in primary education, and, as determined in 2011, it needed to increase the budget for education by over $7.3 million USD in order to reach the target set by the Millennium Development Goals at the end of 2015 (PDP, 2011). 86.4% of Filipinos are functionally literate, but literacy is “much higher among those in the highest income stratum and who completed high school or higher education (Ibid.).” In 2009, the number enrolled in higher education rose to 2.62 million, and access to higher education was increased through scholarships and financial aid programs (Private Education Student Financial Aid Assistance Program and the President Gloria Scholarship, for example) (Ibid.). There is much more access to educational institutions and financial help in urban centers like Metro Manila. However, education sectors, even in the NCR, face challenges with “limited participation of the industry sector in developing competency standards and curricula, the need to upgrade courses and make them internationally comparable, and the need to increase the quality and relevance of education and training programs (Ibid.).” Thus, education to provide technically trained workers at levels from technician to engineer for employment in the energy sector is currently insufficient in Metro Manila and the Philippines.

5.5.3. Issues with Capacity

Metro Manila has had issues with meeting capacity in the past leading to brownouts and blackouts. Brownouts could last for 10 hours or more in 1992. Demand exceeded the system’s capacity by almost 50%. This had a huge impact on industrial and commercial enterprises in Metro Manila. The loss was calculated to be approximately $1.6 billion USD in 1992 (Mouton, 2015) . While the number and frequency of outages has declined since the privatization of the sector, capacity is still a major concern. The demand for electricity increases as the population of the region grows, both from natural growth and immigration. There are also efforts to provide access to electricity for everyone. According to the Manila Observatory, the energy consumption of Metro Manila was 14,924,617 MWh in 2000 (Ajero, 2000) . Using a geometric model, energy consumption was projected to be around 21, 500,000 MWh in 2020. This is a 44% increase in consumption (Ibid.).

As of 2012, the installed capacity on the island of Luzon was 11,739 MW, and the dependable capacity was 10,824 MW. To meet current and future energy demands, there are plans to install 6819 MW between 2013 and 2020 (Petilla, 2013) . Unfortunately, just over 50% of these projects are dependent on coal, and another 37% are dependent on natural gas. Metro Manila’s reliance on coal is expected to increase significantly.

This could cause issues of national security as the region becomes more dependent upon foreign coal. The Philippines do have some coal reserves, potentially 746 million metric tons; however, a large portion is under the Philippine Sea, and extraction in general could be difficult and costly (DOE, 2008). As of 2007, imported coal made up 10% of the energy mix, and local coal less than 5%.

A separate but important issue is fuel used in low-income households. In 2004, 36% of the urban poor were using kerosene as their primary fuel type (Lumampao, 2004) . They purchase kerosene because they can buy it in small amounts; however, it is expensive when purchased in this way, which means that they are paying a premium for their energy.

5.5.4. Issues with Access

The Philippines has a very high cost of electricity. Currently the rate is around P10.52 or $0.22 USD per kWh, which is twice as high as some states in the US. The rates are so high that some people either can-not afford electricity or spend most of their income on it. According to MERALCO, the high rates are caused by three issues: lack of government subsidies, the high cost of supply (fossil fuels), and geo-graphic challenges (MERALCO, 2015) . In the past, MERALCO has faced issues with providing electricity access to all people. It had a lifeline subsidy scheme, which used money from other customers to provide discounted rates based on usage (Mouton, 2015) . This lifeline also covered loss from people pilfering electricity, tampering with meters and not paying their bills (Ibid.). MERALCO has employed several additional methods, including putting meters on telephone poles and requesting people to turn in pilferers, that have reduced their non-technical losses (Ibid.). Even though there has been a decline in the amount of non-technical losses, the rate of electricity loss is still extremely high. This leads to many people not having access to electricity.

5.6. Objectives

The issues and problems faced by the energy sector in Metro Manila are extremely diverse. In an attempt to address as many different types of issues as possible, four objectives were developed:

To encourage education about energy and consumption;

To support energy related research;

To help increase current energy capacity through renewable sources, and

To address issues of access to electricity.

5.7. Solutions

Solutions to energy related issues were generated in relation to the four objectives. Solutions focus on promoting energy related education and job growth, identifying energy sources within the Philippines, including renewables, reducing the demand and consumption of energy, and helping disenfranchised groups gain access to electricity. In this section the full range of projects is explored with the intention of selecting a few to develop further.

5.7.1. Research

Many opportunities presented themselves and were considered as strategies to meet the first and second objectives. Those research opportunities included funding research on renewable energies that were possible to harness, researching and developing a system based on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Environmental Management System (EMS), deciding whether or not to implement regulations or just have companies set their own goals should an EMS be created, establishing a home energy audit program and home energy efficiency research and information team, and researching a way to implement a public/private partnership that would consult and recommend solutions to private renewables companies. Plans to address and decrease brow- nouts and blackouts due to lack of maintenance, insufficient supply, and weather related damage were also considered. Related to insufficient supply, is a larger research project that addresses and evaluates the fully functional Bataan Nuclear Power Plant. The plant is not presently being operated, but is open to the public “as part of the government’s information, education, and communication program on nuclear power,” (which is peculiar because the government has been the main critic and negative voter on reopening the plant). Since 1986, the plant has been maintained and the reactor on preservation mode, costing about $850,000 - $1.1 million USD a year (NPC, 2014). The plant could potentially be operated in the near future if inspections went well and the plant was cleared to receive fuel.

The Philippine government has passed several bills and issued a number of executive orders to support research concerning energy efficiency and alternative energies. Senate Bill No. 1602 is “an act to support the research and development of new industrial processes and technologies that optimize energy efficiency and environmental performance, utilize diverse sources of energy (Reyes, 2013) .” One solution would be using funds to support renewable energy research. Also, providing funds for this type of re-search sends a strong message that renewables are an important issue.

5.7.2. Education

“Skilled workers and firms will flock to and concentrate in cities with high quality of life, increasing productivity and contributing to the financing of further social amenities and public goods (UN-Habitat, 2015).” Many of Metro Manila’s most talented and educated workers leave the Philippines to study and work abroad. The pay is higher, the conditions are better, and more opportunities are available to them overseas. Providing a way for these advanced skills to be obtained and for workers to stay in the NCR would not only benefit the energy sector, but the region as a whole. Therefore, education is one of the most important objectives that were selected. Because of the unprecedented need for educated workers and for individuals to understand energy consumption and use, educational programs considered included investing in training and education for technical professionals, providing a way for students to intern or participate in a work study/co-op, and providing scholarships, first and foremost, to promote equity and provide the opportunity for higher education in engineering or other appropriate fields. The hope is to select candidates of diverse socio-economic backgrounds and give them the opportunity to enter the energy field. There is also a need for consumer education about their energy habits and how they can reduce energy consumption at home. There are many different factors that influence people’s consumption patterns, and it is hard to address all of them. However, if people could be approached directly and educated on energy efficiency, then not only could they have lower energy bills, but energy use during peak hours could also be reduced.

5.7.3. Increasing Capacity

One of the goals of the Department of Energy (DOE) is to “switch from fossil fuel-based technologies to renewable energy technologies in power generation… (DOE, 2008) .” The DOE wants to increase the amount of renewable energy in the mix to 50% by 2030 (Dancel, 2015) . Different renewable and alternative energy pro- jects considered include: solar panels and solar water heaters, wind turbines, geothermal for electricity generation, hydroelectric, hydrogen fueled cars and public transportation, bio-digesters, landfill gas collection, nuclear, natural gas, gravity powered lighting and micro-movement generators. A range of projects has been considered-from the small human scale to the large energy mix scale. The goal is to identify projects that could be implemented at different scales and with different end users in mind.

5.7.4. Community Engagement and Access to Electricity

As mentioned above, MERALCO already has a lifeline charge built in to pay for people using less than 100 kWh and to cover any technical and non-technical losses, including energy prefilling (MERALCO, 2015) . Currently, with the privatized energy industry, people can negotiate and choose from whom they purchase their electricity (generation). The down side of the current organization of this program, though, is the exorbitant amount of electricity that needs to be consumed to qualify as what EPIRA calls a con-testable customer. A user must have “a monthly average peak demand equal to or greater than 1 MW, or after 2014, 750 kW (KPMG, 2013).” After 2016, market performance would be evaluated, and the threshold gradually reduced to meet household demand. The average Philippine home uses 211 kWh (Wootton, 2013) , which, if the threshold were to stay 1 MW, would power upwards of 3000 homes. In comparison, 1 MW in the United States would power between 750 and 1000 homes, which use an average of 911 kWh a month (USEIA, 2015). In Metro Manila, it would take many years to reach the end goal of providing competition at the residential demand level. However, to expedite this process, if people were able to come together as a group, they would have more leverage. This could be done at the barangay level.

6. Water

6.1. Background

The water sector in Metro Manila faces challenges not unlike those of other developing countries: unreliable access to potable water at affordable rates. This is compounded by a rapidly growing urban population, many of whom occupy informal settlements without a household, pipe borne supply. The NCR is the most densely populated region in the Philippines with 18,165.1 persons/km2 spread over an administrative land area of 636 km2 (Asian Development Bank, 2014) . This scenario describes a metropolitan population suffering from constant water insecurity.

Prior to 1997, Metro Manila’s water was supplied by the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System (MWSS), a subsidiary of the Department of Public Works and Highways. This public agency had a record of poor service and mounting levels of debt in the hundreds of millions of dollars. Until 1997, MWSS only served two-thirds of the Metro Manila population or 6.3 million persons. The remaining 3.3 million lacked connections to a pipe-borne supply and were forced to source water else-where. Privatization was viewed as a viable solution, and, in 1997, was implemented employing a con-cession model whereby the Metro Manila region was split into west and east service areas to be managed by two separate concessionaires until the year 2022. The Concession Agreement obligations were to treat and distribute drinking water and to manage bill collection and sanitation/ sewerage services.

6.2. Major Problems

6.2.1. Non-Revenue Water

Non-revenue water (NRW) is defined as the difference between the amount of water put into the distribution system and the amount of water billed to consumers (Espiritu, 2011) . This water is lost from the system through leakage, theft or mismanagement and, therefore, not billed. Prior to privatization, NRW was 60% but today stands at 29.4% under Maynilad Water Services Inc. (MWSI) and approximately 11% under Manila Water Company Inc. (MWCI). NRW can be considered as being either physical loss or apparent loss. Physical losses refer to the loss of actual water as a result of leakages in pipes. Apparent losses refer to loss of revenue exemplified by unbilled water due to data or meter errors and system flushing and theft (Ibid.). NRW contributes to the problem of only 68% of customers in the west region receiving a 24 hour supply. This gap between demand and supply results in water being purchased from illegal vendors at exorbitant prices or stolen from network lines via unauthorized connections. NRW detection is important to mitigate the reduction in water allocations that occur as a result of water shortages that arise due to environmental issues.

6.2.2. Rapid Urbanization

Rapid urbanization is placing significant pressure on Metro Manila’s water infrastructure. Since 1997, MWCI has made steady improvements and remained profitable while MWSI has consistently lagged behind. In 2010, however, MWSS approved a 15-year Concession Agreement term extension to MWSI to continue operations (Maynilad Water Services Inc., 2010) . At present, an estimated 3.3 million people in Metro Manila’s western region live without a reliable 24-hour water supply. With the over three-quarters of the national population projected to live in urban areas by 2030, the challenges of urbanization will undoubtedly be amplified in this region as infrastructure struggles to keep pace with the projected increase in inhabitants.

6.2.3. Affordability

To ensure that operations can continue sustainably, water service providers must charge tariffs allowing them to recover their investments, which include government-regulated profits. The cost of water is heavily subsidized with the poorest customers paying approximately 24% of the cost of connection. The Philippines has the significant intra-urban inequality and associated high levels of poverty (Asian Development Bank, 2014) . This means that its most vulnerable inhabitants are not truly able to afford water or other basic urban services. Furthermore, water service providers are unable to maintain or increase service coverage without a tariff-paying customer base from which to recoup their costs.

6.2.4. Potable Water in Illegal Settlements

MWSS, Maynilad, and Manila Water Company (MWCI) often refuse to extend water infrastructure to illegal settlements due to their illicit nature as well as their impermanency. They are also afraid that squatters will steal water from pipes. Additionally, because these illegal settlements are built in areas such as flood plains, railroad track rights of way, and garbage dumps, there is often inadequate space for pipes. Furthermore, workers have a difficult time being able to reach these areas because they are built in dangerous spaces. As a result, the poorest people in society must buy their water from vendors and often end up paying 10 to 25 times more than the wealthiest members of society (Argo et al., 2011) .

6.2.5. Pollution of Waterways

Many of the waterways in Manila have been considered biologically dead due to the amount of trash and pollution in them (The Philippine Star, 2004), but cleaning up the waterways would have many benefits, including helping to refurbish the water table, increasing general health, allowing for better flood drainage during natural disasters, as well as the economic benefits that could come with increased tourism when the environment is more aesthetically appealing. Most rivers in Metro Manila already have their riverbanks cemented to protect the buildings that are built next to them, although the overwhelming majority of these buildings have their sewer systems drain right into the rivers. This is an accepted practice in the Philippines.

6.2.6. Flooding/Natural Disasters

There are six to seven typhoons every year in the Metro Manila, which cause major flooding. Destructive earthquakes, and tsunamis are natural disasters Metro Manila is also prone to, and they can cause extensive amounts of flooding (CIA, 2015). The effect of this flooding is compounded by the extreme pollution in the city. This includes trash blocking drainage systems as well as clogging waterways. Additionally, illegal settlements along flood plains and waterways reduce the capability for drainage during floods (Environment and Natural Disasters, n. d.) .

6.3. Solutions

6.3.1. Institutional Capacity Strengthening

The SUKI Program, developed in 2005, is a program created by MWCI to assist “mom and pop” business operations in becoming established vendors, while assisting water service providers in enhancing service delivery. It is a mutually beneficial program, which serves as an economic development tool while improving the goals of the service provider (Asian Development Bank, 2014) . Since MWSI changed ownership in 2007, new management has orchestrated a series of internal restructurings and capital investments in order to reduce NRW levels, boost customer service, and make the company profitable once again. $760 million USD were invested in capital expenditure projects between 2008 and 2012 aimed at replacing and rehabilitating deteriorated networks and lines. The introduction of District Metered Areas (DMAs), similarly employed by MWCI, allowed for the subdivision and localized management of network rather than a highly centralized, bureaucratic approach (Espiritu, 2011). MWSI formed partnerships with labor unions, which not only achieved technical goals, but helped improve management and employee relations as well. These partnerships specifically helped to resolve leak detection issues, worker compensation and benefits, employees’ rights and legal services and workers’ security at job sites (Ibid.).

It is recommended that the above mentioned programs, currently executed by both concessionaires, be enhanced and expanded to help manage existing and future infrastructure demands, service delivery and customer satisfaction challenges. Furthermore, independent audits and evaluations should be conducted to ensure compliance with MWSS Regulatory Office obligations and harmonization with regional planning and growth management efforts.

6.3.2. Water for the Community Program Enhancement

“Tubig Para Sa Barangay” (TPSB), or Water for Low Income Communities, is an initiative developed by MWCI that has successfully increased water access for poor and low income communities. This was achieved by removing a critical barrier to the connection application process?proof of land ownership (Asian Development Bank, 2014) . A successful launch and adoption of the land tenure mobile application proposed by the poverty alleviation team earlier would see many more persons receiving household connections. Another crucial element of the TPSB Program is flexible financing plans for connection with the customers opting to pay either an upfront fee of $33 USD, or pay the fee in installments over a period of 36 months. This works out to less than $1 USD per month (Ibid.).

MWCI was able to access a grant through the Global Partnership on Output-Based Aid (GPOBA) pro-gram of the World Bank, thereby subsidizing the cost of connection ($100 USD per connection). The value of this grant was $2.8 million USD and impacted the lives of 1.7 million people. Utilizing this impact as a benchmark for the cost providing affordable 24-hour access, it can be estimated that $6.4 mil-lion USD (adjusted for inflation) would be needed to provide reliable access to approximately 3.3 million underserved customers in Metro Manila’s western region. Further development of urban centers within or bordering the NCR should promote denser development using green building practices where feasible. Such an approach would reduce demand on capital investments in water network infrastructure for future development in this rapidly developing region.

6.3.3. Waterway Rehabilitation

To combat the pollution of waterways, steps should be taken to implement the Clean Water Act, RA 9275 (Environment and Natural Disasters, n. d.) . This would be accomplished through the organization KapitBisig Para saIlog Pasig Project (KBPIP). KBPIP, along with multiple donors and participants, including MWSS, Manila Water Company, Maynilad, IBM, Citibank, the Department of Tourism, SC Johnson, McDonalds, Unilever, and almost 200 other local and international partners, has already done an extremely efficient job of improving the quality of the Pasig River (KapitBisig Para saIlog Pasig, n. d.) . This program should be continued for the Pasig River, as well as replicated in other area rivers, be-ginning with the San Juan, Parañaque, and Marilao Rivers (Ibid.).

6.3.4. Stabilization Ponds

Stabilization pond technology or “lagoons” is a natural method for wastewater treatment that requires a considerable amount of space and is, therefore, not generally suitable for urban areas. It can treat municipal wastewater, industrial effluent or polluted storm water. After treatment, the effluent may be returned to the environment as fertilizer and irrigation water. In this case, the Marilao River has potential for implementation of this measure because it has sufficient space in the area. These areas can be used to build stabilization ponds to treat polluted water from Metro Manila.

6.3.5. Constructed Wetlands

Constructed wetlands are treatment systems that use natural processes involving wetland vegetation, soils and their associated microbial assemblages to improve water quality. In this case, the river best suited to support a constructed wetland is the Parañaque River because of its close proximity to the mangrove swamp and estuary.

6.3.6. Polluter Pays Program for Industrial Waste in Rivers